- Articles Index

- Monthly Features

- General History Articles

- Ancient Near East

- Classical Europe and Mediterranean

- East Asia

- Steppes & Central Asia

- South and SE Asia

- Medieval Europe

- Medieval Iran & Islamic Middle East

- African History (-1750)

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Early Modern Era

- 19'th Century (1789-1914)

- 20'th Century

- 21'st Century

- Total Quiz Archive

- Access Account

Leisure activities in Pompeii and Herculaneum

By Alexander J. Knights, 4 December 2007; Revised

In Pompeian and Herculanean society, leisure activities were an important component of everyday life. Leisure activities entertained, occupied and created a purpose in life, illustrated by an anonymous Pompeian graffito artist – "Baths, wine and sex corrupt our bodies, but make our lives worth living"[1]. Leisure and recreation was influenced predominantly by Hellenistic and Latin influences[2]. Pompeii and Herculaneum, two towns set in Campania, "a fertile region so blessed with pleasant scenery"[3], experienced numerous occupations, each contributing this Hellenistic and Latin influence. Hellenistic influence on leisure can be primarily seen in the presence of Palaestrae in both Pompeii and Herculaneum. From the Latin influence stems the Gladiatorial games, the Munera. Characteristics of both cultures brought about unique forms of leisure -such as bathing complexes and Theatre- modified to suit the ideals of the Roman culture. An amalgamation of archaeological, epigraphic and literary sources corroborate and enable one to attain a real idea of the function of leisure complexes and activities in Pompeii and Herculaneum. But how significant a role did leisure and recreation actually play in Pompeian and Herculanean society? Was it an integral ingredient in the shaping of a unique culture? This essay will cover the above four aspects of leisure activities in Pompeii and Herculaneum -exercise, theatre, gladiatorial games and bathing- and in turn will determine the significance and role of leisure in everyday society.

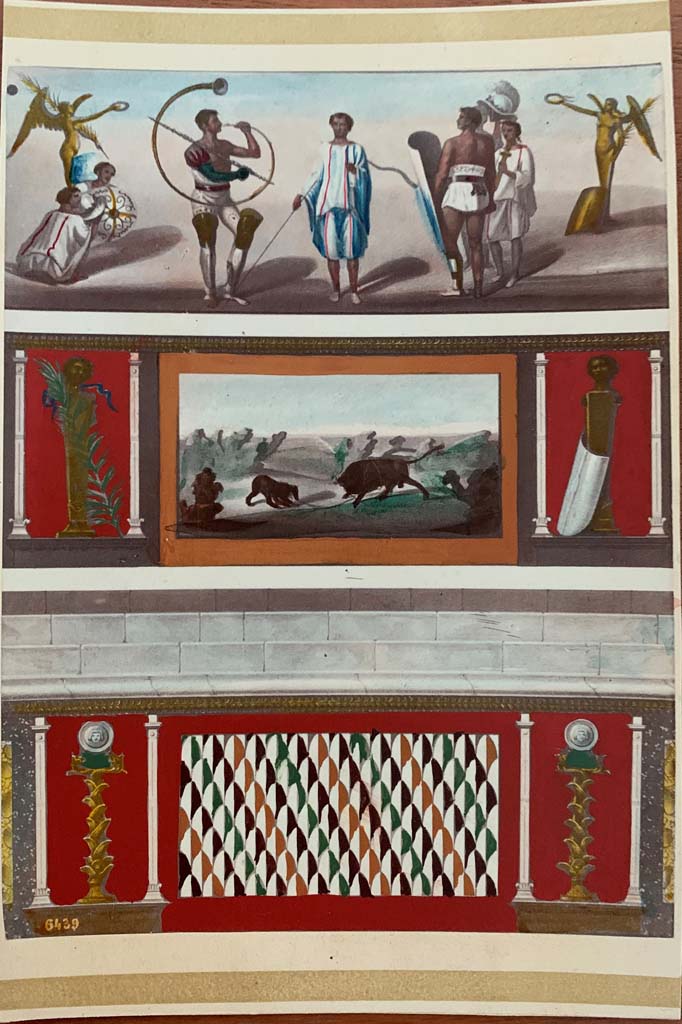

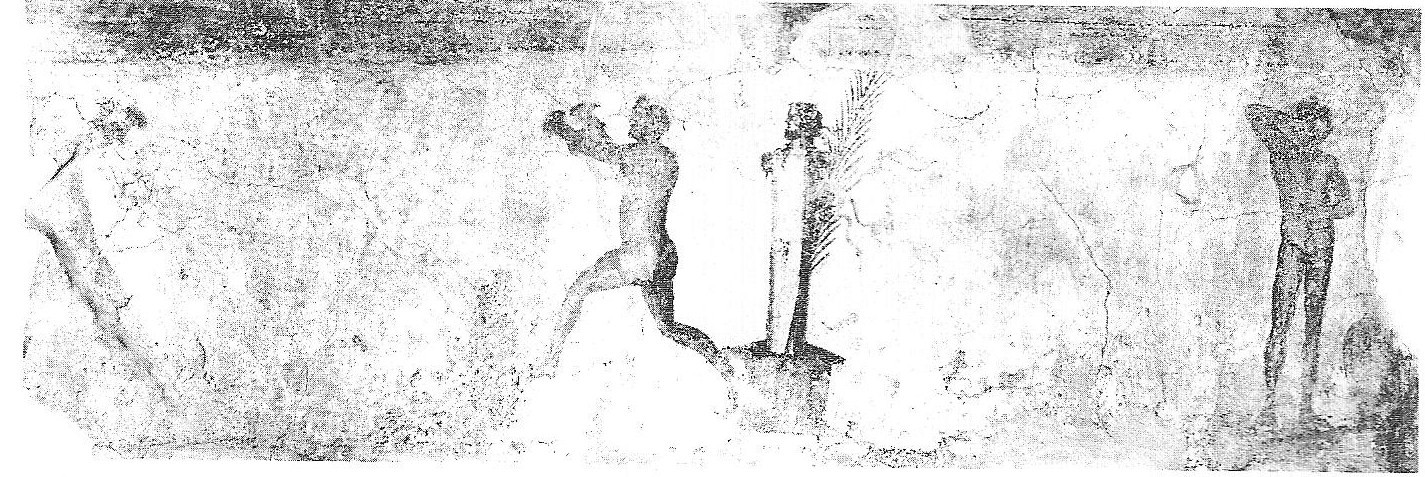

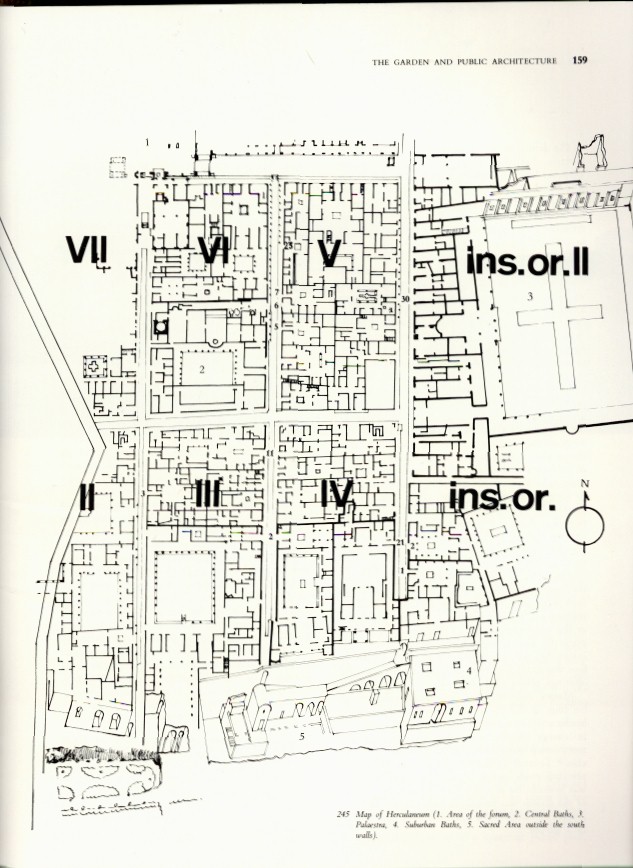

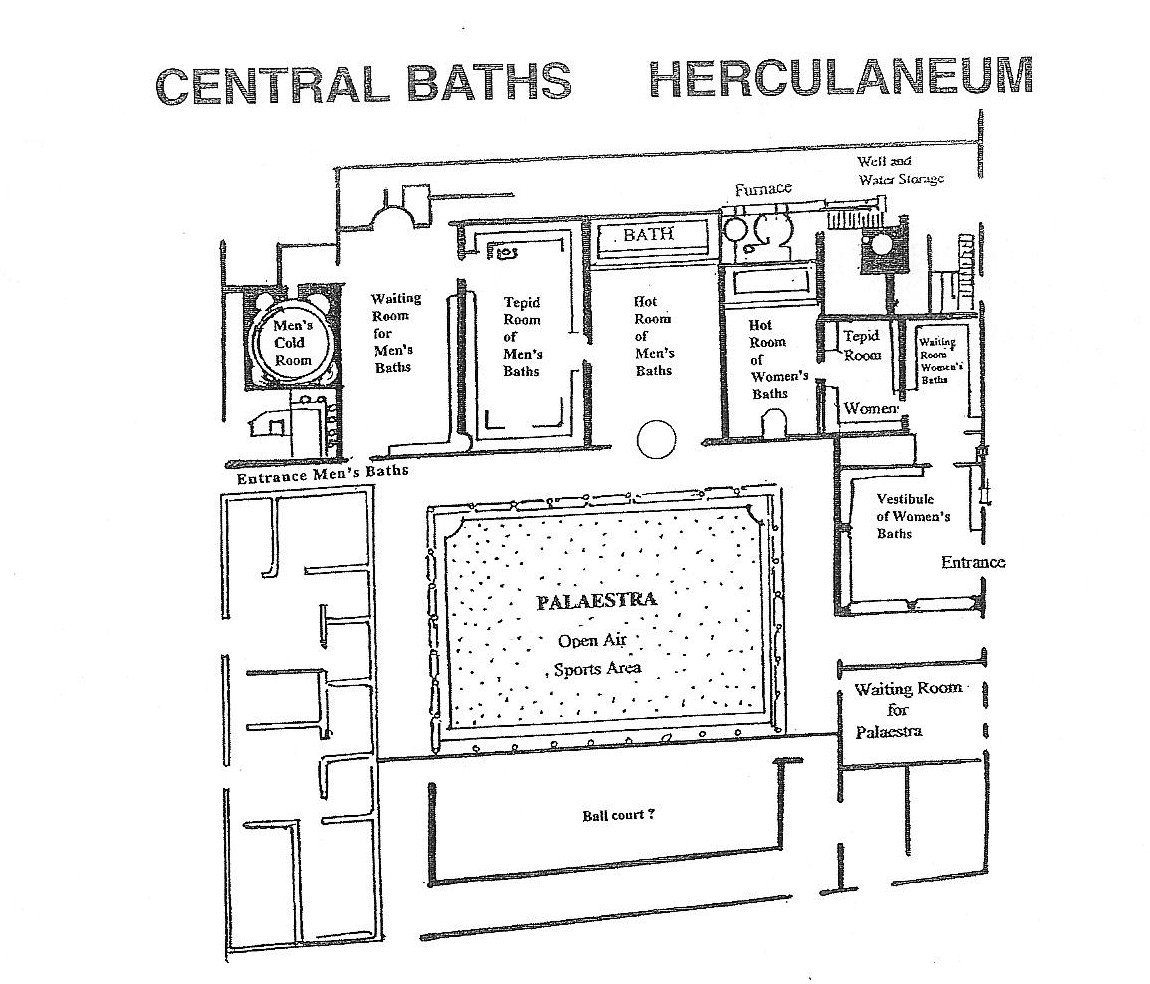

Firstly, Pompeii and Herculaneum experienced strong connections with Greek societies and culture throughout their history, and as a result, Hellenistic influences are evident in their leisure activities. No where else is this cultural influence more obvious than in the presence of Palaestrae – "a public place for training or exercise in wrestling or athletics"[4]. The Palaestra has its origins in the Greek Gymnasia, a complex from Ancient Greece served the same purpose – exercise and training. Several Palaestrae can be found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, with a number being a part of Bath complexes, depicted in the Central and Suburban Baths of Herculaneum, as well as the Stabian Baths in Pompeii[5]. The three acre Great Palaestra at Pompeii is the grandest of all, located in the south-eastern corner of Pompeii. Appendix I depicts a scene from a Pompeian Palaestra, where in which two figures are carrying halteres, or weights. This illustrates just one of the myriad of activities undertaken in Palaestrae – athletics, wrestling, boxing, swimming and even gladiatorial training. The main Palaestra at Herculaneum is situated in the north-east corner, occupying an entire insulae, or block, and is evident in Appendix II. It consists of a large, open space for exercise, and a central cross-shaped swimming pool. Palaestrae were places for recreating and socialising, as well as keeping physically fit, which according to Archaeology of the Roman Empire was "regarded as of great importance in the ancient world"[6]. So it is clear that in everyday life in Pompeii and Herculaneum, the role of Palaestrae as a place of leisure, was significant. This is exemplified by the aforementioned importance of exercise, as well as the copious number of Palaestra complexes.

Secondly, the Latin influence on Pompeii and Herculaneum’s leisure activities is illustrated clearly by the Gladiatorial games held there in Amphitheatres. The Munera were Roman games specifically featuring Gladiators, wild beasts and fighting. These took place typically in an Amphitheatrum, translated as “place for viewing from all sides"[7]. Both Pompeii and Herculaneum had an Amphitheatre, though the on at Herculaneum is yet to be excavated. With their origins in Etruscan culture, Gladiatorial bouts lucidly illustrate the influence of Latin culture on Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, Pompeii was among the first settlements to construct a permanent Amphitheatre, in 70BC, and Appendix VII shows the inscriptional plaque recording this. The Munera were very popular with the fanatical masses, and graffiti from Pompeii gives one a vivid and personal opinion of certain gladiators from the time – "Celadus the Thracian makes all the girls moan"[8]. However, Pompeians were notorious for their over-enthusiasm regarding the Munera, and in AD59 a riot broke out between Pompeians and Nucerians at the Amphitheatre, as seen in Appendix VI. From this, one can attain a perfervid image of the role leisure, namely the Munera played in the lives of Pompeians and Herculaneans. This fed a large and profitable network of gladiators in Pompeii, and Barracks were eventually erected. The vast amount of armour and representations of Gladiators preserved in Pompeii are a testament to this. So, it is blatantly evident that the Munera were a key aspect of everyday life in Ancient Pompeii and Herculaneum, as is attested in the primary archaeological, epigraphic and literary record.

Thirdly, the Hellenistic and Latin influences have also integrated to produce unique renditions of leisure within Pompeii and Herculaneum. The idea of theatre has its origins in Classical Greece, where plays would be acted out in front of male audiences. In Pompeii, plays were largely substituted by new forms of theatre such as ‘pantomime’ and musical acts. While the Theatre at Pompeii was built in the fashion of earlier Greek ones –into a natural hillside-, the later Roman Odeum was built from scratch on flat ground. Elements of both cultures amalgamated to produce an idiosyncratic idea of theatre within Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Herculanean Theatre is yet to be excavated, and thus does not provide any insight, but on the other hand, the Pompeii’s Greek-style Theatre and Odeum have both been excavated. A vast array of masks, mosaics and statues found in Pompeii and Herculaneum give one a salient perception of the illustrious and elaborate nature of theatrics. Statues[9] show some dress styles of actors, as does the amber statuette in Appendix X. As in Hellenic theatre, masks were primary conveyers of emotion and expression. This practice was adopted in Pompeii, among mime artists and acrobats too. Appendix X also depicts some wall paintings of both tragic and comedic mask styles. Theatres were open to women as well as men, evident from Suetonius’s The Divine Augustus, in which he states that “[women must be seated in] the upper part of the theatre, although they formerly used to take their places promiscuously with the rest of the spectators"[10]. Clearly, theatre in Pompeii and Herculaneum constituted for a major part of leisure activity, inherent to the cultural integration evident in the region.

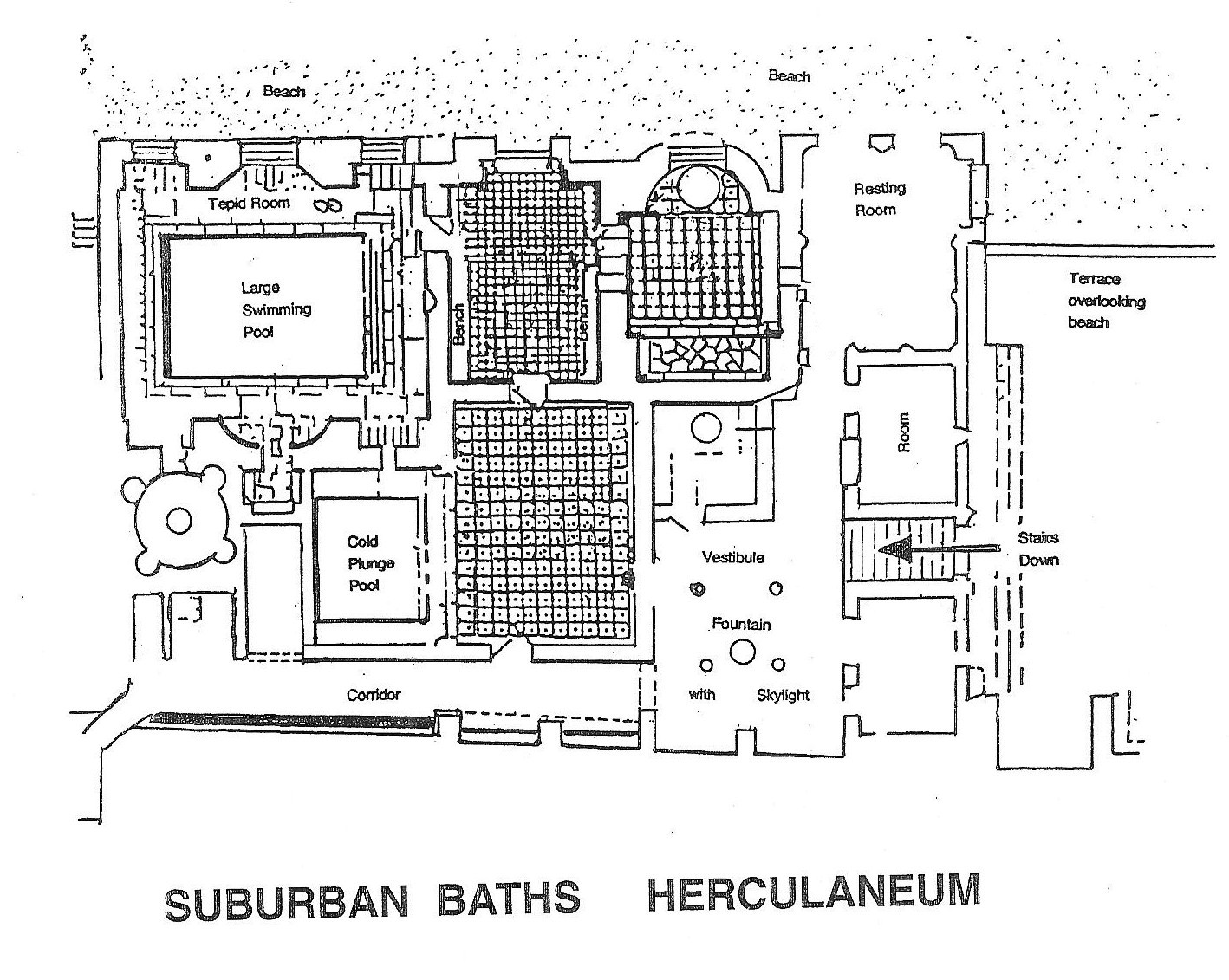

Fourthly, of all the leisure activities in Pompeii and Herculaneum, bathing was both the most revolutionary and extravagant in nature. Though stemming from Greek origins, Baths, or Thermae, were revolutionised by the Romans, particularly in Pompeii and Herculaneum. The reason for this is stated assuredly by Joseph Deiss; “No people in European history were as clean as the Romans for no other people went to the lengths to provide mass bathing facilities…we can only marvel at their costly and elegant bathing establishments"[11]. Many self cleaning implements[12] have been discovered in Pompeii, such as tweezers, scoops, razors and strigils. The intricacy of bathing complexes meant they could include a hot bath (caldarium), warm bath (tepidarium), cold bath (frigidarium), sweat room (laconium), male and female changeroom (apodyterium), swimming pool (natatio) and exercise area (palaestra). The aristocracy recognised the importance of the Baths to the people, that they held ‘free-entry’ days and funded Bath construction. The existence of change rooms and bath rooms for both genders in the Suburban and Central Baths in Herculaneum, and the Pompeian Stabian Baths[13], illustrates the fact that both men and women could attend the baths. Apart from bathing, one could exercise in the complementary Palaestra, where ball games such as pila and trigon were played, along with other sports. A key Roman innovation in Baths was the addition of ‘central heating’ beneath the floors, known as hypocausts. Tile stacks[14] supported Bath floors, under which a furnace burned, to heat up the room. The importance of hygiene and the innovations in bathing complexes illustrate the significance of Baths as a place of leisure in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

In conclusion, Pompeii and Herculaneum both exhibit an array of recreational activities, each influenced by a share of Hellenistic and Latin culture. The archaeological, epigraphic and literary records corroborate to clearly demonstrate that leisure played a monumental role in the daily lives of Pompeians and Herculaneans. It is the conglomeration of Hellenistic and Latin cultural influence which carves out their identity, whether it is through innovation or adoption. While they are major aspects of leisure activities in Pompeii - Palaestrae, the Munera, Baths and Theatre are not the sole forms of entertainment. Seldom were there few sources of recreation, as the Romans enjoyed their leisure time. Juvenal once said, "there’s only two things that concern them: bread and circuses"[15], and this applies perfectly to the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum, to whom leisure activities were clearly a tremendously indicative component of everyday life. Appendices

I. Wall Painting: Palaestra Scene. <Ward-Perkins, J, Claridge, A, Pompeii AD79, Australian Gallery Directors Council Ltd, Sydney, 1980.>

II. Layout of Herculaneum. <

III. Central Baths of Herculaneum diagram. <Class Handout>

IV. Suburban Baths of Herculaneum diagram. <Class Handout>

V. Stabian Baths Diagram. < Wheeler, M, Roman Art and Architecture, Thames and Hudson, London, 1964, p107>

(j: Palaestra)

VI. Wall Painting of Amphitheatre Riot in Pompeii, AD59. <Brilliant, R, Roman Art from the Republic to Constantine, Phaidon Press, London, 1974, p80.)>

VII. Plaque in the Pompeian Amphitheatre. <http://www.pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/R2/2%2006%2000%20p4.htm>

“Caius Quintus Valgus, son of Caius, and Marcus Porcius, son of Marcus, in their capacity as quinquennial duumviri, to demonstrate the honour of the colony, erected this sports complex at their own expense and donated it to the colonists for their perpetual use”

VIII. Gladiator figurines [283-286] and a helmet [287] from Pompeii <Ward-Perkins, J, Claridge, A, Pompeii AD79, Australian Gallery Directors Council Ltd, Sydney, 1980.>

IX. [295, 296] Terracotta statues of actors found buried at Pompeii. < Ward-Perkins, J, Claridge, A, Pompeii AD79, Australian Gallery Directors Council Ltd, Sydney, 1980.> X. Amber statue of an actor [297], Mosaic of a play rehearsal [298], Theatrical masks in wall paintings [299-301] and a scene from a comedy [302] from both Pompeii and Herculaneum. < Ward-Perkins, J, Claridge, A, Pompeii AD79, Australian Gallery Directors Council Ltd, Sydney, 1980.>

XI. Roman hygiene implements: Strigil, Tweezers, Razors, Scoops. < King, A, Archaeology of the Roman Empire, Bison Books Ltd, London, 1982, p121.>

XII. Hypocaust system in Pompeian Bath <http://wjcl.org/pictures/3-30-2006-304.jpg>

Pliny the Elder, Natural History: A Selection, Penguin Group, London, 1991, trans. K. Mayhoff, 1905, p43 This source can be considered reliable, in that it is a translation of a primary source from the time period being studied. Though it contained a lot of content regarding the region in question, very little information about Pompeii and Herculaneum were present. Nevertheless, it provided some useful quotations about the physical environment of Campania.

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars: Divine Augustus, trans. A, Thomson, R, Worthington, New York, 1883. Available from: <http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/suetonius-augustus.html> Suetonius is a rather controversial character, but nonetheless, being a primary source, deserves some amount of credibility. By only using a single objective quotation from his works, I managed to avoid bias on his part. The Divine Augustus was useful because I used in for one purpose – finding a specific quote.

For Archaeological and Epigraphic sources, see ‘Appendices’. [Includes Graffiti, Plaques, Wall Paintings, Architecture, Mosaics, Artefacts and Diagrams]

Adkins, L, Adkins, R, Introduction to the Romans, Sandstone Books, Leichardt, 1996. This book is aimed at a teenage audience, and thus simplifications are evident in it. Although, the book was thorough in certain areas, such as baths. It acted as a starting point, where from which I could extend my knowledge on the topic in question. Its authors are both archaeological consultants, hence its reputable credibility.

Brilliant, R, Roman Art from the Republic to Constantine, Phaidon Press, London, 1974. I found this book at Macquarie Uni Library, but it proved to be of little use. I managed to photocopy one image from it, but other than that, it was of no aid information-wise. The image is reliable because it is attested in numerous other books – the riot at the Amphitheatre in AD59.

Deiss, JJ, Herculaneum, Italy's Buried Treasure, Getty Trust Publications, Los Angeles, 1989. This particular book was of great use. Not only did it give some valuable quotes, but also ideas. The information is reliable because the author is a Masters graduate, and thus has some experience and knowledge in the area of researching. Of course there is biased, but it is less rampant in this book. All in all, this was a very convenient book.

Drinkwater, JF, Drummond, A, The World of the Romans, Cassel, London, 1993. This book provided an in-depth look at Roman society and culture. It is a very credible source, produced by PhD graduates, and this increases its reliability. While it is a very reputable source, it failed to give much information solely into Pompeii; leisure activities in particular. Therefore, though it is a useful book, it did not prove useful for the means of this essay.

Harris, N, History of Ancient Rome, Chancellor Press, London, 2003. This was a tremendously useful book, covering a vast range of Pompeian related topics. This included leisure to an extent, proving it to be helpful. Though a secondary source, this book incorporated a lot of primary information. It seemed quite reliable in terms of its information, and from the praises it has received, is a fairly reputable piece of work.

Hurley, T, P Medcalf, C Murray & J Rolph, Antiquity 3, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2005. This is the school textbook. It was useful in getting a hang of the basics, enabling me to expand to more in-depth sources. The authors integrate a lot of primary information, and are credible writers and historians, making for a very reliable book.

King, A, Archaeology of the Roman Empire, Bison Books Ltd, London, 1982. This book was arguably the most valuable in terms of images and basic information. It had an entire chapter on Leisure and entertainment, providing me with a range of images and quotes about the matter. It is a well accredited book, primarily written objectively, though bias does enter at times. All up, it was both a extremely useful and reliable source.

Liberati, AM, Bourbon, F, Rome. Splendours of an Ancient Civilization, Thames and Hudson, London, 2005. Liberati is the director of the Museum of Roman Civilisation in Rome and Bourbon is a graduate in literature, ancient archaeology and classics. This makes this particular book very credible, but with a slant of bias towards Rome. It was of some use in terms of information, but overall, was not terribly worthwhile.

Ramage, NH, Ramage, A, The Cambridge Illustrated History of Roman Art, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, 1991. I attained this book from Macquarie Uni Library, and it turned out to be quite useful for Baths. I photocopied some images and diagrams of Baths in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Because I did not attain any written information, I avoided any bias or impartiality. Thus, it was both useful to an extent, and credible.

Reader's Digest, Vanished Civilisations, Reader's Digest Services Pty Ltd, Surrey Hills, 1988. This book had a chapter dedicated to Pompeii, as it is a ‘vanished civilisation’ in a sense. It focuses a lot on the eruption of Vesuvius, but does talk about daily life too. I managed to obtain some questionably subjective information about aristocratic views of leisure activities, and motives involved in their funding. It is a well accredited publication nonetheless, and hence was reliable to a certain level. This book was also rather unhelpful, but did provide some secondary information on entertainment.

Rodgers, N, Life in Ancient Rome. People and Places, Hermes House, London, 2006. Rodgers has written a very valuable section on Baths and Theatre in this book and one would seldom find bias in relation to facts about these aspects of daily life. The book was reliable, which was an added bonus. Ultimately, it proved to be of great use.

Toynbee, VMC, The Art of the Romans, Thames and Hudson, London, 1965. This book from Macquarie Uni Library proved to be all but useless in the end. It isn’t that it had no useful images or information, but I had already obtained it from other sources. So, it eventuated to be of virtually no use other than as an attesting source.

Ward-Perkins, J, Claridge, A, Pompeii AD79, Australian Gallery Directors Council Ltd, Sydney, 1980. This, along with the ‘Archaeology of the Roman Empire’ book, would have to be the most useful. It provided a vast array of primary epigraphic and archaeological sources from Pompeii and Herculaneum. I scanned and used a lot of them in the Appendices. Being solely images, bias and impartiality are avoided. All in all, it was a fantastically valuable source of literature, containing useful images.

Wheeler, M, Roman Art and Architecture, Thames and Hudson, London, 1964. The only thing extracted from this source was a diagram of the Stabian baths. It was rather not useful apart from that one image. Again, being an diagram, it is typically free of bias.

Grout, J, Amphitheatrum, 2007, retrieved 26 November 2007. Available from: <http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/amphitheatrum.html> This website is still in its initial stages, and is run by an enthusiast rather than a professional historian. Therefore, its information needs to be taken with a grain of salt. However, the information about the Amphitheatre which I gathered from there was able to be attested by other, more reputable sources. So, the information used was reliable, and useful.

Dunn, B, II.6 Pompeii Amphitheatre, Date Unknown, retrieved 2 December 2007. Available from: <http://www.pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/R2/2%2006%2000%20p4.htm From this website I got the image of the plaque in the Pompeian Amphitheatre. For this, it was useful, as I could find it no where else. The image was reliable, as it is a primary epigraphic inscription, found on site.

Batzarov, Z, Ancient Graffiti on the Walls of Pompeii, Date Unknown, retrieved 2 December 2007. Available from: < http://www.orbilat.com/Languages/Latin_Vulgar/Texts/Pompeii_Graffiti.html> This website was the source of my graffiti inscription about the Gladiator Celadus. This piece of graffito is evident in numerous other secondary sources, clarifying it as a reputable translation.

Kreis, S, A brief social history of the Roman Empire, 2006, < http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture13b.html> This is where I obtained the Juvenal quote from. It is a very well known quote, and its authenticity can be attested by hundreds of other secondary sources, as well as Juvenal’s own writings – the Fourth book of Satire. References and Notes:

| |||||||||||||||

http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110Tech/RomanAfrica2/map2.jpg>

http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110Tech/RomanAfrica2/map2.jpg>

>

>