Forgotten Civilizations of Meso-America

With the wealth of writing about Meso-America being on Aztecs, Mixtecs, Toltecs, Zapotecs, Maya and Olmecs, other equally great Meso-American peoples have not made it to the popular mind. This article looks at other equally great but lesser known civiliasations that rose an flourished.

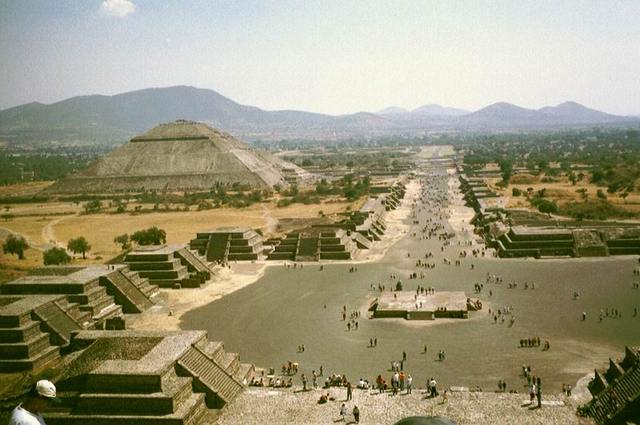

Teotihuacan 200 BC - 800 AD

Teotihuacan was Mexico's greatest indigenous civilisation. Founded about 200 BC in the valley that bares it's name, a strategically important access point between major Puebla and Mexico valleys, the huge metropolis dominated Mexican life for half a millennium. Reaching it's zenith in the 5th and 6th centuries, its influence towered over both the Maya and Zapotec alike. Teotihuacan is most remembered in the modern mind for the legacy it left Mexico, not just Mexico’s, but some of man's greatest achievements to this day, the Pyramids of the Sun, Moon and Quetzalcoatl. But, it also left Mexico one of it's greatest mysteries, as to the civilisation’s demise around 800 AD.

Unlike most civilisations in Meso-America, Teotihuacan was not just a city state. Extending far beyond the valley of Teotihuacan, a Metropolitan Area of citizens inhabiting a number of cities and rural lands covered the Central Plateau, as well as much of Hidalgo to the north. Teotihuacan is considered nowadays by archaeologists to have been a true nation state. The state had, over the centuries, picked up many colonies, conquered outside cities and placed strong military garrisons around the country. But, it would be wrong to call Teotihuacan (as it often is) an empire. Unlike many past and contemporary cultures and most later ones, there are few traces of a cult of the warrior existing within the city. Teotihuacan, instead, was a trading superpower, it dominated Mexico as a manufacturing giant and industrial base of factories and industry. A whole district of the city was an industrial park of workshops. Teotihuacan's goods were exported all over Meso-America, the styles of it's art and architecture have imitations in almost every city.

How the city of Teotihuacan was able to forge a nation in a world that managed nothing beyond aristocratic empires, city states and the odd kingdom before is a testimony to its real greatness. Of the thousands of artistic finds in the city, sculptures, murals, paintings, many in private apartments, the theme of Teotihuacan art is almost entirely religious and incredibly upbeat, though just before the end it took on a dour and sinister turn.

Most Meso-American cities were simply religious centres of temples and palaces for the aristocracy with the mass populous living in mud huts and wooden shacks on the surrounding farmlands. In this sense, Teotihuacan was a true metropolis, the citizens living in modern apartment blocks in the city centre. The quality of the peasant dwellings indicates the distribution of the wealth was much more even than other cultures. Modern archaeologists are tending towards the view Teotihuacan was a religious state welded together by a powerful common religious devotion. A parallel could be drawn between Teotihuacan and Angor, a city of similar size in an unfeasible jungle location forged upon the common devotion to a god king.

Why Teotihuacan fell is still a hotly debated mystery, but most of it's 200,000 inhabitants abandoned the city leaving it to the jungle. No one common cause for this exodus seems to exist. Over population beyond the resources is a popular solution, loss of faith is another. Teotihuacan art also took on a military edge in it's final death throws, so military historians look to either barbarians or civil war for answers. Much of the city shows signs of destruction, statues of deities defaced, and structures burned to the ground. It is known the exodus from the city was gradual, so it's been suggested a period of decline and mass depopulation. Also, the city lost domination of its outer provinces quite a while before its fall, whether the signs of destruction in the city were caused by an outside invader preying on the dying city or done by the priests symbolising the gods abandoning them is, perhaps, something we will never know. Ice records show no major climatic change occurred in Mexico at that time, though there may have been a prolonged drought.

Angor too suffered collapse, abandonment and loss to the jungle. Like Teotihuacan, overpopulation, conquest by neighbour and overexertion of resources have been blamed for its demise. But with Angor, thanks to Chinese writings by merchants in the city, it is known, shortly before it fell, that the city was suffering terrible resource problems caused by its jungle location, repeated incursions from barbaric Thais, and the monarch of the city converted to Buddhism from Hinduism and lost his godhood.

Teotihuacan's fate, though, wasn’t unique in Meso-America. Just a century later, a similar fate would befall the Maya cities and Monte Alban. For a while, after its fall, an estimated 30,000 people still lived in ruins, some former city residents, some primitives from outside. The later rulers of Mexico, the Toltecs, capital city, Tollan, only had a population of 30,000 at its peak.

Xochicalco 250-900 AD

Another contemporary dinosaur flourishing alongside Teotihuacan, Xochicalco was to outlive its trading partner by just a century. A highly spread out site positioned upon a fortified hilltop, the city shows great influence from all parts of Meso-America. Boasting architecture in Mayan, Teotihuacan, El Tajin and Mixtec styles, it truly was the crossroads of the New World. Known as the mysterious city because, despite being one of the most flourishing civilisations in Mexico for nearly a millennium, it left hardly any inscriptions to bare testimony to former glories.

The Aztecs had a legend of Tamoanchan, the gathering place, where the survivors of Teotihuacan assembled and there undertook to like apostles to spread to the four corners of the known world to keep alive the teaching of the great civilisation before one day returning to refound the great city. Recent archaeological finds tantalisingly suggest Tamoanchan may have been Xochicalco.

Xochicalco is located very close to Teotihuacan and, in many military history books on Meso-America, is blamed for the downfall of Teotihuacan, finding it hard to believe there was not fighting between the two rivals so close together, theorising Teotihuacan must have conquered Xochicalco, and, in turn, Xochicalco destroyed Teotihuacan in a war of independence.

Contrarily to this, the Xochicalco site itself, devoid of water like so many Meso-American cities, seems just to have been a ceremonial centre for the priest/nobility supported by cultivation of the lowlands around. The population fluctuating between 10-20,000 hardly gives it a great base for conquering the 1.4 million inhabitants of the Teotihuacan Metropolitan Area.

Cholula 100 BC - 1519 AD

If Teotihuacan had a natural successor it was Cholula. Located in the rich Puebla Valley, Teotihuacan’s closest major neighbour, the exact relationship between the two cities is unknown. Whether Cholula was the second city of the state or independent neighbour with tributaries of its own remains unclear.

The region around the city was first settled around 1500 BC and the site itself about 400 BC. In about 100 BC, two villages unified to form the bases for the city, which was to survive until 1519 AD, earning it the description as the 'eternal city'. The great pyramid is larger even than the Pyramid of the Sun or the Great Pyramid at Giza and one of the largest man made structures on Earth. Cholula flourished as a contemporary and partner of Teotihuacan and briefly became the centre of Mexican civilisation after its fall, but quickly went into decline. Whether its decline was a co-symptom of Teotihuacan or for different reasons is unknown. However, it was to survive its decline, was reinvigorated by the settlement of the Olmec-Xicallancas in the valley around the 9th century AD, and was to become a main thorn in the side in its time for both the Toltec and Aztec Empires. Briefly conquered by the Toltecs in 1168 AD, it sowed the seeds of demise for the Toltecs Empire and, with the aid of other cities in the valley, it successfully expelled the invaders and, subsequently, restored itself to its former glory with its conversion to the cult of Quetzacoatl brought to it by its Toltec conquerors.

Cholula, in its final phase, became a holy city and place of pilgrimage. It fought a bloody war with the Aztecs and resisted conquest until 1519, when, in a ploy, it invited Cortez into the city, planning to deceive and ambush him. Unfortunately, Cortez got wind of the plan and massacred the inhabitants, vowing to destroy each of the 365 temples and replace them with churches. Fortunately, he never fully fulfilled his promise.

El Tajin 100 AD - 1200 AD

Capital of the vast Totonac lands, El Tajin can really be described as the first successor empire of Teotihuacan. The Totonacs grew in stature from around the 7th century AD as Teotihuacan's hegemony started to wane. They peaked between the 9th and 13th Century AD, when they rivaled and outlasted the Toltec Empire before their final downfall. The date of their demise occurring so temptingly close to the rise of the Xolotl-Chichimec empire in that area as to theorise more than a coincidence.

Totonac culture impresses even among the best Meso-American cultures. The Pyramid of Niches is arguably the finest crafted in Mexico. Built between 600 and 900 AD, the site boasts a wealth of astronomical references, including the pyramid itself which has 365 niches. The city was obsessed by the Meso-American ballgame, and its ball courts, possibly the most magnificent of all, depict human sacrifice the forfeit of the losers of the game. The style and sacrifice to be copied in both Tollan and its protégée, Chichen Itza.

The city claims several firsts in Mexico, among them the terrible skull racks that decorate the city, a tradition that was to carry both to Tollan and Tenochtitlan and alarm the most hardened Conquistador.

The similarities between Totonac and Toltec culture have not gone unnoticed. El Tajin pre-dates Tollan, but also existed contemporary to it. Similarities of both the architecture built at a later date in Tollan and in Chichen Itza after the Toltec conquest, and the adoption of so many Totonac customs such as the cult of death, has lead to many theories of how the two civilisations interacted. Some historians have suggested EL Tajin was the original home of the Nonoalcas, who migrated to the Valley of Mexico and amalgamated with the Toltecs. Conquest of El Tajin by the Toltecs and adoption of their civilisation is another proposal. This would be highly unlikely due to Toltec resource limitations, though, even more unlikely, they did conquer Chichen Itza. The most reasonable solution is close links, trade and cultural influence between the two vast successor empires.

A criticism of El Tajin could be that it was the first really nasty civilisation in Meso-America, soon to be followed by the Toltecs, and the harbinger of the bloody militaristic turn the country was to decline in subsequent years.

The Olmeca Xicallancas

The Olmeca Xicallancas moved into the lush Puebla Valley from the east around the 9th century. The valley was sparsely populated and seems to have been vacated by the Mixtec migration to Oaxaca. The Olmeca Xicallancas, who don’t seem to have been that numerous, never constructed new cities, but moved into established ones including Cacaxtla, Tlaxcalla and Cholula. Their cities are believed to have functioned as a federation, constantly clashing with the neighbouring Toltec Empire and, effectively, stopping its eastward expansion.

The Olmeca Xicallancas were overran by the Chichimecs migration of the twelfth century. Many fled the valley in response to the invasion, but others, like the Toltecs in the Valley of Mexico, probably amalgamated with the more numerous Chichimecs and formed the bases of their civilisation.

The Huaxtecs

An indigenous Mexican coastal people based in Hidalgo, Veracruz, and San Luis Potosi. Often regarded as a separate Mayan people, due to close links between their languages, they seem to have been a culture slightly apart from the rest of Mexico. Despite the fact they built cities, pyramids and created elaborate artwork, they scandalised conservative Mexico with their embracement of the principles of permanent naturism.

Calling themselves the Teenek, the Huaxtecs were regarded by any decent clean living Mexican to be the scourge of Meso-America. The Aztecs describe their warriors as ‘a screeching bunch of she-devils’ and many Mexican peoples were said to utter the expression 'as low as a Huaxtec'. The reason for this was the Huaxtecs religion based around a cult of sexuality and the penis. Mexican culture was prudish by nature, in most cases deliberately not showing genitalia in art. By the time of the Toltecs and Aztecs, this Puritanism had reached a zenith Calvin would have recognised, lewdness in Aztecs society being punishable by death. So fellow Mexicans seem to have taken to Huaxtec culture, as Cromwell would taken to a Spartan religious festival.

The Huaxtecs emerged as a major people shortly after the fall of Teotihuacan and enjoyed great era of civilisation and military success during Toltec times, eventually being responsible for the destruction of Tollan. They, however, became the whipping boys of the Aztecs in several campaigns causing many of their peoples to flee north to the USA and reduced those that stayed to a client kingdom.

The Chichimecs-Nahuas

Nomadic skin clad tribes living the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the northern deserts occupy a unique place in Mexican history. Charged with the destruction of just about everything that's good in Mexico, Teotihuacan, Toltec Empire, El Tajin, Xochicalco and later becoming the Aztecs, in few accounts of Mexican history they don't play a major role. The Chichimecs, vast in numbers and ferocious in nature, like the barbaric tribes of the Steppes ever drawn to Rome, were ever poised at any time to sweep down and destroy any culture that displayed weakness of spirit.

This evocative image of Chichimecs in much artwork and literature has been at the centre of many accounts of Mexican history. But, just how barbaric the Chichimecs really were is still questionable, many of the romanticisms simply not adding up. Meso-Americans being prone to championing the noble savage just as much as their European cousins. Though, however unbarbaric they do eventually turn out to be, the Chichimecs still were an ever present hazard to any Mexican civilisation that existed. While much of their later villainy is true, what role they played in earlier history is still debatable. One of the earliest incursions attributed to the Chichimecs was around the time of Teotihuacan’s demise. Military historians often forward the fact that mountain top cities such as Xochicalco survived, whereas the lowland Teotihuacan died, to surmise a case for a military destruction of Teotihuacan overrun by Chichimecs, though little evidence for this exists.

Chichimecs-Nahuas were among the founding co-partners of the aggressive Toltec Empire. Consisting of both civilisation and militarism in equal measures, to many it seems almost innate that the famed ferocity of the Chichimecs was the catalyst of Toltec belocracity.

It was as the sun set on the Toltec era that the Chichimecs made their most dramatic entry into the history books and earnt their reputation as the Meso-American Huns. In the great Chichimec migration of the 12th and 13th centuries, they overrun almost the whole of the Central Plateau. The image of the screaming barbarian horde at the gates of Tollan imprinted into the native psyche for generations.

It‘s here the Chichimec barbarity really comes into question. Evidence certainly shows they were no longer wearing skins and displayed many of the trappings of civilisation, both in dress and mannerism. The unruly mass of savages don’t seem to have been totally destructive either. In their conquest of the region they not only destroyed cities but built them, amalgamated with other peoples and entered many existing cities by intermarriage and integration. Their legacy of creation and building stands the test of time, filling Mexico with a higher concentration of metropolis’ than had ever existed. Testimony to this is the wonder in which the Spaniards stared at the Lake Texcoco city complex in1519.

The final phase of the Chichimec saga is as the Aztecs. The Chichimecs, more so than any people in the past, took to the ardour of empire building. For several centuries the empires of individual tribes were built, warred upon and fell to dust until, eventually, an almost complete unification was achieved under a single powerful empire that was to stretch its wings far and wide across the whole of Mexico, the Aztec Empire.

The heritage the Chichimecs left Mexico is enormous. The mighty Aztec Empire, the death cult of sacrifice, the breathtaking architecture of their cities, but, most of all, the cult of the warrior. No matter how civilised they became, the Chichimecs were, at heart, warriors. Their legacy was not the high civilisation of Teotihuacan, nor the wisdom of the Maya, it was a dark violent era that their ascension plunged Mexico into.

|

|