- Articles Index

- Monthly Features

- General History Articles

- Ancient Near East

- Classical Europe and Mediterranean

- East Asia

- Steppes & Central Asia

- South and SE Asia

- Medieval Europe

- Medieval Iran & Islamic Middle East

- African History (-1750)

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Early Modern Era

- 19'th Century (1789-1914)

- 20'th Century

- 21'st Century

- Total Quiz Archive

- Access Account

6. The Qing Empire

By Han_Wudi

Category: East Asia: China

Founding of the Qing Empire

The last native Chinese dynasty, the Ming, was in decline by the late 16th century. Successive famines and other natural disasters like floods, earthquakes and epidemics struck China. The imperial court itself was in chaos, with eunuchs and corrupt officials forming cliques and planning intrigues against each other instead of working for the good of the country. A series of weak or child emperors contributed to the mess. Yet the government still undertook many large and expensive military expeditions, like the 1592 war in Korea. Taxes had to be raised to pay for these, further placing a heavy burden on the common people. For the first time in centuries, too, foreigners entered China. The first visitors were Jesuit missionaries who had come to spread Christianity. The new religion soon gained many converts, but was outlawed when some foreigners began committing crimes in China. Certain papal edicts and customs of Christianity also ran contrary to traditional Chinese values. The Reign of Kang XiKang Xi (1654-1722) was the second emperor of the Qing Dynasty, the son of Emperor Shun Zhi. His father was a mere six years old when put on the throne, and under the control of the regent Dorgon. He died, aged just 24, of heartbreak and smallpox after losing his beloved concubine to the disease. As such, Kang Xi was only seven years old when he ascended the throne in 1662.

Again, the child-emperor was dominated by his powerful regents. Among them was the ruthless General Oboi, who several times tried to usurp power from Kang Xi and installed his henchmen in the imperial court to ensure that one day, he would suceed. Thankfully he never did, for the teenaged Kang Xi arranged his assasination, and seized full power. Yet that was only the beginning of Kang Xi's troubles. In 1674, the Ming turncoat generals Wu Sangui, Shang Kexi and Geng Jinmao led a great revolt against the Qing government. This is known as "The Revolt of the Three Feudatories" in Chinese history. It was among the largest civil wars in history, involving an area the size of the southeastern United States, and more men, weapons and deaths than all the wars of 17th-century Europe. These generals, most notably Wu Sangui, had helped build the Qing Dynasty, and were rewarded with large, almost-independent fiefs, and held the Manchu title of prince. However, they were not satisfied and demanded monetary subsidies from the Qing court in exchange for loyalty; a form of blackmail. When Kang Xi refused, the three rose up in arms. Kang Xi acted quickly and decisively. The army was mobilised and sent against the rebels, with the emperor personally directing the operation. The rebellion lasted seven years, but there was never any real chance of it suceeding. The three generals were unable to coordinate their efforts, and their own greed and incompetence further hampered their individual efforts. By 1681, Wu was dead and Geng and Shang had been captured and executed, along with their sons. Wu Sangui's son fought on for another 32 years but presented no real threat to the Qing Empire. Next Kangxi turned against the last Ming loyalists, based on Taiwan. These were led by the Zheng family, descendents of a Ming general who had earlier surrendered to the Qing. His son, however, fought on to restore the Ming Dynasty. This was none other than Zheng Chenggong, better known in the West as the pirate Koxinga. A capable military leader, Zheng was originally based in Fujian province. However, an unsuccessful Qing attack on his capital of Xiamen persuaded him to look for a safer base of operations. He turned to Formosa, or Taiwan, occupied by the Dutch since the early 17th century. In 1661 Zheng Chenggong launched a massive onslaught on Taiwan. Badly outnumbered and outgunned, and also facing a native revolt, the Dutch were defeated and driven off the island. Zheng Chenggong immediately set about turning it into an advanced base of operations, but he died, in 1664, before this was completed. For the next 20 or so years, led by his widow, the Zheng bloc carried out frequent raids on China's eastern coast with Taiwan as the springboard. Preoccupied with domestic affairs, the Qing Empire was unable to launch an expedition to conquer Taiwan. Finally, with the resolution of the Revolt of the Three Feudatories and the empire prosperous and at peace, Kang Xi ordered the construction of a large and modern fleet with the aim of retaking Taiwan. Zheng Chenggong's successors were not nearly as capable as he was, and intrigues within the Zheng bloc resulted in disunity between his relatives. Thus, the Manchu armada easily conquered Taiwan in 1683. After the victory, Kang Xi turned against the warlike northern Mongol tribes, which were a constant menace on China's borders. He personally led two expeditions which utterly defeated the enemy, ending a long-time threat to the peace and stability of the Middle Kingdom. At this time too, other countries began taking notice of China. Russia's Tsar, Peter the Great, had been despatching large numbers of Cossack cavalrymen to the banks of the Amur River with the aim of taking Southern Siberia from the Chinese. Kang Xi, however, desptached troops that defeated the Russian armies and gained Southesatern Siberia for China. During the 61-year-long reign of Kang Xi, China saw unprecedented growth and prosperity. The population soared to well over 100 million, and China's borders were greatly expanded. Arts and culture flourished, for Kang Xi was also a superb poet and essayist who actively promoted learning and literature. Among his great cultural contributions was the commissioning of the Kang Xi Dictionary, a volumnious book on the Chinese language that is still in use today. As such, the Emperor Kang Xi is regarded as one of the greatest rulers China has ever had. A man of great military and intellectual abilty, he led the Middle Kingdom into a Golden Age that spanned over a century.

|

Yong Zheng

|

Yong Zheng was a very hardworking emperor. He made many contributions during his short reign, namely, the establishment of a defence/war ministry and the determination of a border with Russia. He also thought of a way to choose the successor to the throne secretly; this would prevent any power struggles such as those which had plagued him.

The economy grew greatly during the reign of Yong Zheng. Kang Xi's rule was consolidated and the empire became stronger and wealthier than before. Yong Zheng died in 1735 at the age of 57, having ruled China for 13 years. It was said that he was found slumped over his desk, a pen still in his hand, literally dead of overwork.

The Reign of Qian Long

Emperor Qian Long

|

On coming to the throne, Qian Long continued to work with his father's and grandfather's domestic policies, but did much to chang the foreign policy of the Qing Empire. During his reign, China's borders reached their greatest extent. The Qing Empire encompassed Korea, Mongolia and all of modern China; an area of 12 million square kilometres, and most Asian countries like Burma and Vietnam paid tribute to the Qing.

The reign of Qianlong was also a time of great economic prosperity for China. Building on the solid economic foundations laid by Yong Zheng, Qian Long expanded and diversified the economy and developed agriculture, to great success. Population soared; by the late 18th century over 300 million people lived in China. Being a great patron of the arts and culture, Qian Long also contributed greatly to a cultural Golden Age, with new styles of painting and building being developed.

After the glittering century-long rule of the three emperors Kang Xi, Yong Zheng and Qian Long, China seemed the most powerful country in the world. It produced all it needed; there were hardly and imports, and still had plenty left to trade with the European states. Yet in the later years of Qian Long's reign, the seeds of decline were sown.

Decline of the Qing Dynasty

In the 1790s, China seemed a vast and powerful state. China seemed incomparably ancient and enormously rich. It traded silk, lacquer, porcelain and tea to the western traders, but scarcely needed them. The Qing dynasty of the Manchu's had brought a reign of peace and prosperity that had seen the number of Chinese multiply to over 300 million, making China the most populous nation on Earth.Beijing, the Manchu capital, was a magnificent city. The streets, which bustled with traders during the day, were normally quiet and safe at night. The city was full of gardens and bridges. Unlike many other large cities in the world, it was very clean, as a special detail removed all horse droppings and other refuse. The streets were well policed, crime and civil disorder were almost non-existent. The shops were full of goods, and they streamed with banners.

The Qing government was arranged thus: the President of every ministry was a Manchu, supported by a Chinese vice president. There were in effect, two governments ruling China- the visible outer government, characterised by it's well ordered bureaucracy. There were in fact 18 grades of bureaucrat, with prestige and salary to match. Most government service positions were chosen on the basis of examinations taken Confucian philosophy and morality. It was hoped in this way that able and honest men would serve China. There was a civilian administration and a separate military establishment. The civilian administration was divided into two parts- the first was the 6 boards or Ministries, each run a by a Manchu and a Chinese Vice-President. Each had its own function, personnel, revenue, rites, war, public works and punishments. There was no equivalent of foreign affairs- foreigners were expected to pay tribute, and had no other role. In the second category was the censorate. The task of the censors was to weed out corrupt bureaucrats and review policy. They even had the right, even the duty, to criticise the Emperor's policies- although this was a very rare occurrence. Helping the censors in their task was the fact that any official, however lowly, had the right to send memorials directly to the Emperor- an effective way of dealing with corruption.

Within the Forbidden City, lay the inner court and secret government, outside of the eyes of nearly everyone. Within sat the Emperor, his court and his wives and concubines, and other instruments for controlling the bureaucracy. Above the board were the grand secretaries. Originally assistants hired or fired at the shim of the emperor, they had gradually increased their powers and status, to become the equivalent of a Western cabinet, but by the reign of Ch'ien Lung, they had also been superseded by the grand council, a new authority of 6-10 people, Manchu and Chinese, some of whom may also have been grand councillors.

The Westerners who visited Peking were suitably impressed by what they saw. English ambassador Lord Macartney left this account of a meeting with the Emperor Qian Long:

"His approach was announced by drums and music. He was seated in an open palanquin carried by 16 bearers, attended by a number of officers bearing flags, standards and umbrellas, and as he passed we paid him our compliment by kneeling on one knee, whilst all the Chinese made their usual prostrations.

We sat down on the cushions at one of the tables on the Emperor's left hand: and at other tables, according to their different ranks, the chief (Manchu) princes and the Mandarins of the court at the same time took their places, all dressed in the proper robes of their respective ranks. These tables were then uncovered and exhibited a sumptuous banquet.

The emperor sent us several dishes from his own table. The emperor's manner is dignified but affable and condescending and his reception of us has been very gracious and satisfactory. He is a very fine old gentleman, still healthy and vigorous, not having the appearance of a man more than 60.

The order and regularity in serving and removing the dinner was wonderfully exact and every function of the ceremony was performed with such silence and solemnity as in some measure to resemble the celebration of a religious mystery."

Yet amidst all this glory, corruption that would lead to the sad decline and eventual fall of the Qing Dynasty was beginning. And the fault, partly, was the Emperor Qian Long's.

In 1775, the Emperor Qian Long, then 65 years old, took fancy to a young man called Ho Shen, forty-three years younger than him. Ho Shen was reportedly feminine in appearance, with very fair skin and long, red lips. There was also a rumour, whispered among the commoners, behind the emperor's fascination with this man.

It was said that when Qianlong was still a young prince in the palace, he ran one day into the room of a lady-in-waiting just as she was putting on her make-up. Being young and playful, he decided to play a prank on her, and tiptoed from behind to scare her with the fright. The lady-in-waiting jumped at the sudden shock and turned round, touching the future emperor. Another passing court lady witnessed this breach of protocol and reported it. The lad-in-waiting was demoted, and unable to take the humiliation, hanged herself one day. This incident had a profound imperssion on Qian Long, and it was said that he found Ho Shen to be very similar in appearance to the court lady whose death he had caused. Perhaps he thought Ho Shen was the reincarnate of the court lady and his guilt overcame his common sense.

Whatever the cause, Ho Shen became the emperor's new favourite. He was showered with gifts and the emperor indulged him in whatever he wanted. Ho Shen was a greedy man, and he began the large-scale corruption and nepotism that was to bring down the ruling house of Aixinjueluo.

He abrogated powers and official posts, including that of Grand Councillor, for himself and his family and cronies, and regularly stole public funds and taxes. The old emperor still trusted him implicitly and listened only to him. Bribery became widespread, and taxes were raised again and again. The peasants suffered. Soon though, their suffering was compounded by severe floods of the Yellow River, and indirect result of corruption as dishonest officials pocketed funds meant for the upkeep of canals and dams. The price of rice went up, and many were soon starving.

The problems corruption caused were further worsened by the fact that China was simply overpopulated, and many were homeless vagrants, creating large-scale social problems very difficult to deal with. By the turn of the century China had lost its shine.

The White Lotus Rebellion

The White Lotus was a religious sect, which combined elements of Bhuddism, Taoism, and a few doomsday prophecies. The most important tenet of their creed was that the ultimate reincarntaion of Buddha as Maitreya would come soon, ushering in a new government and peace and plenty. This was not a doctrine that pleased Qian Long, so in 1775 it was banned. However, in the 1790s it began to reappear, due to mostly to the efforts of it's new charismatic leader, Liu Chi-seh, a gifted orator and able strategist. He proclaimed that the Maitreya was incarnate in the son of his own master Liu-Sung, and second, that he had discovered a surviving member of the Ming dynasty who was in fact the legitimate emperor. The authorities were not pleased by this, and so in 1793 a renewed crackdown on the White Lotus was proclaimed. However, the new crackdown unwittingly played into the hands of the White Lotus. In the central provinces of China, although a nuisance, they had little chance of succeeding in open rebellion. So they fled to the outer provinces, where the control of the Q'ing was weaker.

Because of the population growth, there had been significant internal migration within China. People had left the heavily populated plains, rivers and valleys for the less populated border, desert and mountainous regions, such as the border areas of Szechwan, Kwangsi, Hunan and Kweichow. Although the imperial bureaucracy tried to control these areas, there were too few of them, and the country was wild, plagued by bandits. A state of semi-warfare existed between the native populations and the new settlers. Almost everyone carried weapons, and knew how to use them. These regions had always been somewhat rebellious, but previously these had been suppressed by the formidable Manchu Banners. It was to these regions that the White Lotus fled.

Attempting to destroy the White Lotus, the local authorities launched crackdowns on the White Lotus rebels in the border areas. However, the methods they used were basically a reign of terror, with the result that many border villages armed themselves against Imperial forces, effectively joining the White Lotus in rebellion. In early 1796 many villages openly joined the rebellion, leading to a full scale revolt.

At first, the White Lotus's tactics were simple- they would attack valley towns, sack them, murder any Q'ing officials, and disappear to their own well fortified mountain villages. The sect later allied itself with armed bands proficient in martial arts. Later, well armed bandits, smugglers and other criminal groups which the government had been trying to suppress joined the White Lotus. The Miao aboriginal people, along the Hunan-Kweichow border revolted against the newly arrived Chinese immigrants and the imperial structure the Q'ing was trying to impose upon them. Although unaffiliated with the White Lotus, their rebellion added to the problems of the Q'ing.

The Emperor, although unaware of the seriousness of the rebellion, realized that it must be put down. Unfortunately, he relied on Ho Shen for information and guidance, and appointed Ho-Lin, Ho Shen's brother, and Fu-k'ang-an, a Manchu with links to Ho-Shen, to lead the campaign. These two, with Ho-Shen's help, rather than outfitting their armies, stole the money for themselves. The Qing troops, untrained, with antiquated weapons, led by corrupt generals were no match for the White Lotus. There were many defeats- which Ho Shen told Qian Long were victories.

Finally though, after the ascension of the new emperor Jian Qing, and his punishment of Ho Shen, the revolt was put down. Local gentry and militia were mobilised instead of the earlier method of using the Qing Banners, and villages were fortified. This negated the White Lotus' guerilla tactics, and by 1805 the revolt had ended.

However, China's problems hadn't. Jia Qing tried hard to restore the flagging dynasty after taking the throne in 1796, but for the first three years was hampered by Qian Long, who had abdicated and become the emperor-father (in reality he still held the reins of power) because, out of respect and filial piety, he did not wish to reign longer than his great grandfather Kang Xi.

After Qian Long's death in 1799, Jia Qing wasted no time in getting rid of Ho Shen. He and most of his cronies were speedily demoted, arrested or exiled, and he himself was condemned to death. However, Jia Qing, deferring to respect for his late father, aloowed the man most singly responsible for the Qing Empire's parlous state to commit suicide.

Although hard working and conscientious, the new emperor was unable to halt the decline of Q'ing China. Perhaps due to conservatism, many practices continued unchanged. The once-elite Manchu Banners had proven worthless. However, to disband them and recruit a new army would be to admit that the Q'ing dynasty was a mere paper tiger. And so the expensive, but useless Banner's continued on the Imperial payroll. Equally as bad, because peace in the border regions was guaranteed not by Imperial forces but by mercenaries and local militias, the seeds of China's later regional warlords had been sown.

There were other problems, such as the yellow river floods and the lack of rice. There was however, an easy, simple and cheap solution. Rather than going up the tortuous canals and the Yellow River, the rice could go by sea. Originally, the prevalence of pirates had been a factor for the land route, but this was no longer the case. Governor's of maritime provinces sent submissions to the Emperor proposing a sea route. The corrupt administration in charge of rice memorialised against it. And perhaps because change was bad, the rice still went up the unreliable Yellow River, and bribes were extorted by corrupt officials.

Superficially, China still seemed rich and powerful. But it was now in a terminal decline. Lord Macartney's mission to open China to British trade had been a failure. In the Opium war, less than 50 years later, the British blasted there way into Chinese markets. The corruption of the administration, the poor army and the resistance to change eventually meant the end of Imperial China.

China in the 19th Century

China had been in decline since the late 18th century, and this continued into the 1800s, despite the Jia Qing emperor's best efforts. Corruption was simply rooted too deep in the civil bureaucracy to be cleared out, and China's military was but a paper tiger, their antiquated guns unable to match the powerful modern weapons of the Europeans. And so the 19th century was a period of slow but sure decline and humiliation for a country that had once been the world's leader in innovation, technology and economics. An empire that had lasted through over four thousand years of rich history and culture was destined to become a semi-colony, carved up by the Western powers, while corrupt officials gorged themselves on public funds and weak emperors sat on the Dragon Throne.So let us examine some of the significant events during this century.

The First Opium War 1839-42

China at this point had some contact with outsiders, but Britain's first attempt to open up trade failed (see above), over a disagreement over protocaol when the foreign envoys met the emperor. The general feeling in China was also that they did not really need trade, for China was largely self-sufficient. However, there was a great demand in the Western countries for Chinese tea and porcelain. The British, frustrated by what they saw as one-way trade and the Qing government's stoic refusal to open up more ports to them, decided to use opium, produced in India, to barter for tea and porcelain instead.This was highly profitable for the British, but it soon turned China into a drug-crazed nation: thousands of sleepy addicts roamed its streets, creating great social problems, and the crime rate rose as poor addicts tried to get money by hook or by crook.

In 1839, a talented and righteous official by the name of Lin Zexu took charge as the Imperial Commissioner at Canton, a major trading hub. He was horrified by the extent of opium addiction he discovered, and immediately took steps to stop it. The most dramatic of this was the burning of over 200 cases of opium at Tiger Gate in May 1839.

Naturally, this incident greatly heightened tensions between Britain and China. The British were disgruntled that China had repeatedly refused to discuss treaty relations between the two countries, and the Chinese, for their part, saw the Europeans as uncultured barbarians. These issues, combined with the opium and a disagreement on whether British nationals who committed crime on Chinese soil should be tried by Chinese courts, ignited the Opium War.

The war began in November 1839 and soon proved how backward the Chinese army really was. They were completely no match for the modern British gunboats and weapons, and soon found themselves utterly defeated both at sea and on land. The Treaty of Nanking, ending the war, was signed in 1842. It was the beginning of what Chinese would call "unequal treaties" with the foreign powers, because it was the foreigners who benefited the most from these scraps of paper.

Its first and fundamental demand in the treaty was for British "extraterritoriality"; all British citizens would be subjected to British, not Chinese, law if they committed any crime on Chinese soil. The British would no longer have to pay tribute to the imperial administration in order to trade with China, and they gained five open ports for British trade: Canton, Shanghai, Foochow, Ningpo, and Amoy. No restrictions were placed on British trade, and, as a consequence, opium trade more than doubled in the three decades following the Treaty of Nanking. The treaty also established England as the "most favored nation" trading with China; this clause granted to Britain any trading rights granted to other countries. In addition, Hong Kong was "leased" to the British for a hundred and fifty years; it was only returned in 1997.

The Second Opium War 1856-60

What is sometimes called the Second Opium War was, in reality, nothing more than a series of skirmishes between Chinese forces and British and French troops. Yet it ended in 1860 with China forced to sign even more unequal treaties, with the Western powers dictating the terms and reaping the benefits. Apparently though, it also showed that the Qing government had learnt nothing from their defeat in the first war. Corruption was still widespread in the armed forces. Despite being blamed and demoted after the first war, Lin Zexu agitated for the adoption of western weapons and military methods, but the high-ranking mandarins turned a deaf ear to him.And so China weakened, and continued to do so until Sun Yat Sen's rebellion suceeded in 1911.

The Taiping Rebellion

The next calamitous upheaval to occur in China was the Taiping Rebellion, which lasted over fifteen years and directly or indirectly caused the lives of an estimated 20-odd million Chinese. It is still the bloodiest civil war ever to occur in history.The Taiping Rebellion was started in 1850 by a young scholar called Hong Xiuquan. The son of a poor famre who lived near Canton, Hong was a bright student, but repeatedly failed the civil service examinations. One day, he was feeling downcast after one of these failures when he passed by and heard a Christian missionary giving a sermon. He became very interested in Christianity and brought home several books on the subject.

Later, he went for, and failed, the civil service examinations yet again. This is believed to have caused a nervous breakdown during which he saw visions. Whatever the cause, he became convinced that he had met God and was in fact Jesus Christ's younger brother, sent down to earth to eradicate all evil.

Years later, he went to study with a Southern Baptist Minister called Issachar J Roberts, and became even more inspired by Christian ideals. He then proceeded, in his fervour, to found a religious movement, the Taiping Movement or Movement of Great Peace. It is possible that the movement became militant because Hong, for some reason or another, regarded the Manchus as foreigners and demons to be exterminated. Only then, he believed, would the great Kingdom of Heavenly Peace descend from heaven to rule the world.

The Qing government was naturally alarmed by the large following the movement gained, and began harrassing it. In response, Hong began organising a military wing and accumulating a cache of arms. The rebellion officially flared up in 1851 when Hong declared that the era of "Great Peace" had started.

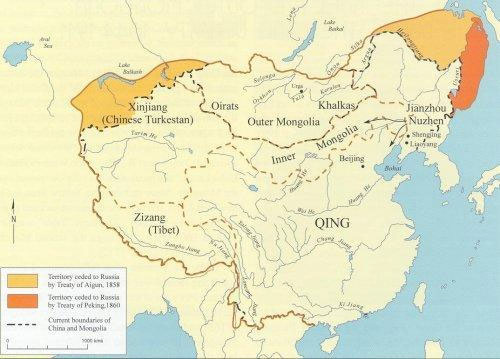

Map of the Qing Dynasty

|

The Kingdom of Heavenly Peace was a theocratic state with the Heavenly King as Absolute Ruler. Its objective, as implied by its name, was the achievement of peace and prosperity in China with all people worshipping the one and only one god. It consisted of a single hierarchy which undertook all administrative, religious, and military duties. The movement was founded on a radical economic reform program in which all wealth was equally distributed to all members of society. Taiping society itself would be a classless society with no distinctions between people; all members of Taiping society were "brothers" and "sisters" with all the attendant duties and obligations traditionally associated with those relationships in Chinese society. Women were the social and economic equal of men; many administrative posts in the new Kingdom were assigned to women This social and economic reform, combined with its passionate anti-Manchu nationalism, made the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace a magnet for all the Chinese suffering under the dislocations and disasters of the mid-century.

At first, the rebellion had great success, as the Taiping soldiers proved to be remarkably disciplined. Much of the Yangtze Valley fell in the first few years of the rebellion, and Nanjing in March 1853. Hong renamed the city Tianjing or "heavenly Capital" and continued his northward march. The rebels assaulted Beijing, the Qing capital, but were defeated.

The next few years were ones of stalemate, with the Qing army unable to beat the rebels and the rebels unable or unwilling to push on northward.

Meanwhile, the movement was disintergrating from within. Hong decided to withdraw from active participation in the governing of his territories, believeing that, as Heavenly King, he should rule by divine virtue. He threw himself into the carnal pleasures of his harem and enjoyment all day long in the palace.

His followers and fellow leaders, too, succumbed to the common human vices of corruption and temptations of the flesh, and the rebellion slowly began unravelling.

This was accelerated by the arrival, from 1860, of a Western-trained and equipped army called the "Ever-Victorious Army" and led by British General George Gordon (he gained the sobriquet "Chinese" Gordon) because of his involovement here). The Taiping Movement lost ground steadily to him and regular Chinese forces with able native generals such as Zeng Guofan.

In 1865, Qing forces captured Tianjing. Hong committed suicide as the imperial forces entered his capital. His hanged themselves. Qing forces went on a rampage, killing a reported 100,000 in a savage sack of the city. The Kingdom of Heavenly Peace had come to an end.

For the next thirty years, Chna meandered along, losing territory to foreign powers, the Qing Dynasty steadily declining in power. Russia gobbled up Siberia and parts of Xinjiang, the British forced more trade concessions upon the Chinese and even the weaker European states like Belgium and Holland muscled in.

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95

Since the visit of Commodore Perry, Japan had modernised rapidly, and become an industrialised nation in less than 50 years. China, on the other hand, had missed out on the Industrial Revolution, and was weak, backward and corrupt. japan's armed forces were modern and trained using Western methods; the Chinese army and navy had antiquated or worse, defective weapons and outdated tactics. So when the two powers went to war in 1894 over a dispute over Korea, the result was easy to predict.Since 1875 China had allowed Japan to recognize Korea as an independent state. Then, as China tried to reassert influence over its former tributary, this provoked rivalry with Japan and a split in Korean public opinion between modernizing reformists and inward-looking conservatives. In 1894 a pro-Japanese Korean reformist was assassinated in Shanghai and a Korean religious sect, the Tonghak, began a rebellion. The Korean government appealed to China for assistance and the Japanese encouraged Chinese intervention, only to send an expedition ostensibly in support of Korean reformists, reaching Seoul by June 8 and seizing the royal palace a fortnight later.

China suffered heavy losses and a humiliating defeat in the short war. In Korea, the Japanese trounced the Chinese army, capturing Pyongyang by late 1894 and meeting only token resistance from the disorganised and ill-prepared Chinese forces. In November the Japanese took Port Arthur (modern Lushun). A draw, with heavy losses, in the Battle of the Yellow Sea and a comprehensive defeat by Japanese land and naval forces in the battle of Weihaiwei convinced the Qing government to sue for peace.

The Chinese were forced to sign the one-sided Treaty of Shimonoseki. Formosa (present-day Taiwan), the Liaodong Peninsula and the Pescadores were ceded to Japan, and Korea became nominally independent, but in reality was a Japanese protectorate. To further humiliate the Chinese, the Japanese insisted that the Qing government pay an indemnity of 200 million taels of silver. However, the Western powers, especially Russia, fearing the rise of Japan, intervened and forced Japan to return the Liaodong Peninsula to China. Japanese dissatisfaction at this was the direct cause of the Russo-Japanese War ten years later.

The war had several wide-ranging repurcussions. In China, students and patriots enraged at the weakness of their country began forming revolutionary movements, one of which, founded by Dr Sun Yat Sen, would eventually bring down the 5000-year-old monarchy. In Japan, the Western intervention began a half-century of unhappiness with the Western powers, which eventually resulted in the Second World War. The war also resulted in the formation of a secret society in China - to be known as the Boxers in Europe.

The Boxer Rebellion

China's defeats and weakness in the latter 19th century resulted in a great outpouring of patriotism. Most of these patriots blamed the foreign powers for China's problems, and began to hate the westerners. At the turn of the century, a spiritual movement known as the Society of Harmonious Fists arose in Shandong province, attracting thousands of followers to its cause to drive the "foreign devils" out of China. Members of this society practised a form of shadow boxing which they believed made them invulnerable to bullets.The movement had the tacit support of China's de facto ruler, the Empress Dowager Cixi (In picture: left). The Empress Dowager had exerted a great influence on the country since the ascension of her son Guang Xu to the throne. The emperor held no power; she did. And she had contributed much to the ruin of the country by being extremely resistant to change; the "Hundred Days Reform" the progressive Guang Xu wanted to initiate to modernise China was stoically opposed and crushed by her; from then on, Guang Xu was kept in house arrest in the palace and she took charge of running the country.

Being resistant to change, she disliked the Europeans and all their technical innovations despite the good they were doing for the country. As such, she took no action when the Boxers entered Beijing in early 1900, and Chinese troops stood by and did nothing or even joined in the assault when large groups of Boxers began attacking the consulates of Britain, Germany, Japan, Russia and the United States.

The assaults were fierce: one American diplomat left this description:

"[The Boxers] advanced in a solid mass and carried standards of red and white cloth. Their yells were deafening, while the roar of gongs, drums and horns sounded like thunder. . . . They waved their swords and stamped on the ground with their feet. They wore red turbans, sashes, and garters over blue cloth. [When] they were only twenty yards from our gate, . . . three volleys from the rifles of our sailors left more than fifty dead upon the ground."

Almost miraculously, the vastly-outnumbered defenders of the consulates held on for two months before an international relief force reached them. Next, this force, known as the Eight Power Allied Forces, occupied Beijing and put down the rebellion. As a result of this event the Open Door Policy was formulated by American Foreign Secretary John Hay. This allowed all nations access to the China market.

The Fall of the Qing Empire

Empress Dowager Cixi died, just hours after her son Emperor Guang Xu, in 1908. With her went China's last strong ruler. Her successor was her young nephew, Pu Yi, just two years old. As he was still young, Prince Chun ruled as regent. Like Cixi, Prince Chun was a conservative. He appointed many conservative officials to important posts and sacked dynamic and progressive leaders like general Yuan Shi Kai, later to play a pivotal role in the Chinese Republic. In 1911 the harvest failed, and China went into a period of great economic difficulty. the authority of the government was clearly tottering.

At this point, Dr Sun Yat Sen returned to China from Hawaii, where he had been in self-imposed exile. He knew that the time for rebellion was now ripe. With his contacts and supporters, he organised it in September 1911.

From then on, the revolt was swift and successful. On October 10, 1911,

soldiers from the Wuchang armoury, led by Yuan Shi Kai, joined in the rebellion. This is known as the "Double Ten" incident in Chinese history. This latest turn of events finally forced the Qing government's hand. Valiant efforts to contain it failed and finally, on February 12, 1912, Pu Yi abdicated, bringing the curtain down on the 270-year-old Qing Dynasty and 5000 years of absolute monarchy in China. His edict of abdication read thus:

"Today the people of the whole empire have their minds bent on a republic, the southern Provinces having begun the movement, and the northern generals having subsequently supported it. The will of providence is clear and the people's wishes are plain. How could I, for the glory and honor of one family, oppose the wishes of teeming millions? Wherefore I, with the Emperor, decide that the form of government in China shall be a Constitutional Republic."

A new republic was formed, with Sun Yat Sen as provisional president. However that was not the end of china's troubles and it faced many more disasters and momentous events throughout the century.

List of Emperors

Nurhachi - reigned 1616-1626

Abahai - reigned 1626-1643

Shun Zhi - reigned 1644-1661

Kang Xi - reigned 1662-1722

Yong Zheng - reigned 1723-1735

Qian Long - reigned 1736-1795

Jia Qing - reigned 1795-1820

Dao Guang - reigned 1821-1850

Xian Feng - reigned 1851-1861

Tong Zhi - reigned 1862-1874

Guang Xu - reigned 1875-1908

Xuan Tong - reigned 1909-1912

Chronology

1644: Li Zicheng captures Beijing; Li Zicheng is defeated by the Manzhou under Wu Sangui.

1661-1722: Reign of Kang Xi.

1670: Kang Xi promulgates the Sacred Edict.

1681: Revolt of the Three Feudatories is suppressed.

1683: Taiwan captured from Guo Xingye.

1699: The British East India Company establishes a trading post in Canton (Guangzhou).

1723-1736: Reign of Yong Zheng.

1728: Encyclopedia published.

1736-1795: Reign of Qian Long.

1755-1759: Chinese Turkestan is brought under Qing control.

1760-1770: Tea trade with Europe increases.

1793: Lord Macartney's (England) embassy is unsuccessful.

1816: Lord Amherst of England's embassy is unsuccessful.

1839: Lin Zexcu is made commissioner in Canton. Opium is burned. British retreat to Hong Kong.

1839-1842: The First Opium War.

1842: Treaty of Nanjing ends the First Opium War

1851-1862: Xian Feng is emperor.

1811-1872: Zeng Guofan, scholar and official.

1812-1885: Zuo Zongtang, leading modernizer.

1823-1901: Li Hongzhang, modernizer and scholar official.

1850-1864: Hong Xiuchuan leads the Taiping Rebellion.

1856-1860: Anglo-French War (The Second Opium War).

1860: Treaty of Tientsin is ratified. Summer Palace is looted by British and French troops. Prince Gong is acting head of state.

1862-1875: Tong Zhi Restoration.

1853-1868: Nien Rebellion.

1866: Navy Yard is established at Fuzhou.

1868-1873: Muslim Rebellion.

1870: Tientsin Massacre.

1872: China Merchants Steam Navigation Company is established.

1875-1908: Guang Xu is emperor.

1838-1908: Cixi (Tz'u Hsi), empress dowager.

1894-1895: Sino-Japanese War.

1896: Postal Service is established.

1898: Hundred Day's Reform.

1898-1900: Boxer Rebellion.

1904-1905: Russo-Japanese War.

1905: Traditional Civil Service System ends.

1912: Overthrow of the Qing Dynasty by rebels led by Dr Sun Yat-sen; China's last emperor Pu Yi abdicates; China becomes a republic with Dr Sun as provisional president.