- Articles Index

- Monthly Features

- General History Articles

- Ancient Near East

- Classical Europe and Mediterranean

- East Asia

- Steppes & Central Asia

- South and SE Asia

- Medieval Europe

- Medieval Iran & Islamic Middle East

- African History (-1750)

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Early Modern Era

- 19'th Century (1789-1914)

- 20'th Century

- 21'st Century

- Total Quiz Archive

- Access Account

The Rivers Ran Through It: Britain's War for Empire in North America

Category: Early Modern: Military History

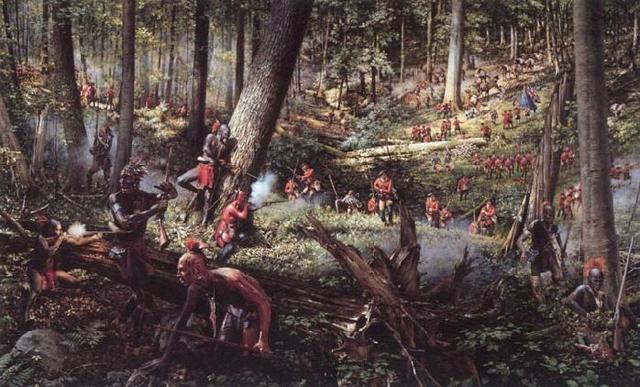

In 1883, Sir John Seeley stated, in The Expansion of Britain, that the British Empire had been acquired in "a fit of absence of mind." By then the sun never set on that imperium, but it had to start somewhere, and that somewhere was the continent of North America. France and England had been natural enemies since the Norman Conquest, interrupted by a time-out for a mutual death struggle with Habsburg Spain from the 1580s to roughly the middle of the seventeenth century. Once the European hegemony of Spain had been superceded by that of France, the contest was resumed, and was transplanted to British and French colonial possessions in North America where the New World seemed to present untold wealth and opportunities. This struggle for empire was as inevitable as were the tides given the mercantile-political and social realities of the eighteenth century. France could not stand by and let the English, Scots and German colonists spread over the continent, expanding up and down the river valleys that were the super highways of the pre-industrial age, dispacing France's Indian allies by means of a land intensive agricultural imperative, and threatening the influence of the French on the vital Mississippi and Saint Laurence Rivers. There was no state of war between France and Britain in 1755 when British regulars arrived in Virginia and marched to the headwaters of the Ohio River to remove a French fortification that blocked the movement of English trade and settlement down the Ohio Valley to the Mississippi. But this was a resumption of the "wars of King William and King George" for presence and territory on the North American continent. The populations of the British colonies were mostly Englishmen and were all British subjects. Their movement west of the Allegheny Mountains was becoming inexorable due to population and immigration pressures. A few French traders and missionaries were not about to stop that. The French encroached on strategic territory claimed by both Virginia and Pennsylvania. The British pressured French interests in territory claimed by the King of France. Something was going to give. New France was vast in extent and impressive on a map, but there were fatal weaknesses in its economy and demographics. The industry of New France consisted mostly of an Indian trade in hard goods and peltry, in fisheries, and in a semi-feudal agricultural regime left over from the seventeenth century, and controlled by a handful of seigneurs. In Canada, the growing season was short, the variety of crops that could be successfully cultivated was fewer than in more temperate southern English colonies, and the creation of wealth was concentrated in few, socially conservative hands that were not inclined to entrepreneurial pursuits. Timbering was negatively impacted by both transportation difficulties and by lack of manpower. This latter was the ultimate fatal weakness. In all of New France, there were about 80,000 French, about 55,000 of them in Canada. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the English speaking colonies had over 1,500,000 permanent settlers, and there was a sizeable amount of ongoing immigration from the British Isles, and also southern Germany from where protestant Germans emigrated in search of more religious liberty. France, on the other hand restricted immigration for her colonial possessions to Catholic Frenchmen only, and there were far fewer immigrants. The French military presence in North America consisted of scattered small garrisons of troops from the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, some regulars at Louisbourg at the mouth of the St. Laurence River, and at Quebec further upstream, and French officers interacting with France's Algonquin allies and other tribes in the interior of the continent. As the Virginia militia had not been up to the task, the dispatch of two British regiments to Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) in 1755 seemed adequate to deal with a small French presence at the origin of the Ohio River. However, General Edward Braddock met with disaster near Fort Duquesne, his force of about 1,200 being ambushed and cut to pieces by around 900 French and Indians. The undoubted superiority of the French king had been demonstrated to the Indians. A new form of wilderness warfare, the asymetrical warfare of its time, had to be recognized, accepted and addressed. Tactically, British officers had something to learn from their bumpkin colonists, and they showed themselves adaptable and willing to change. Strategically, Britain brought her overpowering advantages to bear to destroy the French Empire in North America. As noted above, the river valleys of North America were the routes into the interior of the continent. These were where the land war was fought. The defense of the Hudson River valley against the French presence at Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) was needed to block any direct attack down that river from Canada. That would have cut the colonies in two and endangered New York town. The control of the origin of the Ohio River would conversely cut off Canada from French assistance from the west. In addition, Fort Niagra (near Buffalo, NY) would deny the French control of the Great Lakes and impact their ability to move resources and troops from Detroit to Canada. France had sent around 3,000 regular troops to Canada at the beginning of hostilities in 1755, and with the outbreak of the Seven Years War in Europe in 1756, there was no longer pretense of any peaceful resolution of the small scale conflict on the frontier of north America. The French and their Indian allies managed to drive many English colonists from the lands west of the mountains, killing, burning and kidnapping as they went. The war on the frontiers of New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland became characterized by savagery on both sides in the years 1755 to 1757, with civilians bearing the burden and militia holding the line in most cases. By 1758, a sea change would begin to engulf the French, and the majesty of the King of France in North America would be carried away to the bewilderment and dismay of the American Indian. The advance of the Europeans on the North American continent would never again be impeded. In 1757, a new force of regular British infantry appeared on the Pennsylvania frontier, part of which was composed of four battalions the Royal American Regiment, many recruited from among men who knew the land, the wilderness and the Indians. More and more British regiments were sent to America, until by 1759, there were 25 regiments of regulars as well as colonial militia regiments that far outnumbered the French in North America. France had a major war to prosecute in Europe after 1756, and the British played off Prussia against France by subsidizing Frederick the Great so that Prussia could sustain her war. Resources could then be directed to North America, and the energetic William Pitt, as prime minister, persuaded and cajoled the American colonies to support the war against France in North America. Not all the colonies had been as impacted as Pennsylvania and New York. Over the years 1755 to 1758, the navy was refitted and expanded and brought up to a strength that could not only seal off the entrance to the St,Laurence River and strangle French trade and reinforcements, but could also blockade the French navy in many of her own ports. In North America, the Royal Navy had ports and more sophisticated support in towns such as Boston, Halifax, and Portsmouth from which to operate. The French were hardly helpless, however, and were led by a charismatic officer with the aristocratic appellation of Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm-Gozon de Saint-Veran. France was not about to surrender the Hudson Valley, a direct route not only to New York from the north, but also to the St. Laurence River from the south. A hard fought and bloody enagement was fought, September 6-8, 1758, over the French position at Fort Carillon (Ft. Ticonderoga to the British) between Lake George and Lake Champlain on this strategic route. Montcalm prevailed in strong defensive works against a British force four times as strong under general James Abercrombie. Later that year, however, this position had to be abandoned by the French as they withdrew into Canada and remained on the defensive. In 1758, two other major campaigns turned the tide against France for good. In Pennsylvania, General John Forbes, assisted by a prominent colonial officer, Colonel James Burd, finished a road that directly connected the port of Philadelphia, over the mountain gaps, on the shortest route to the Ohio River at Fort Duquesne. A system of fortified depots was used at intervals to provide a "protected advance" for a force of over 7,000 regulars and militia, a remarkable army for very primitive and difficult logistical realities in the wilderness. At Ligonier, the last depot on this line of protected posts, after a series of vigorous attacks on Forbes's vanguard, the French withdrew from Fort Duquesne in November and destroyed the fortified works. The French were starting to see the overwhelming numerical superiority that Britain could apply, the Americans, both regular and militia, were becoming adept at military affairs, and were far more numerous than any combination of French troops, militia and Indians. France began to pull back into Canada, in the absence of reinforcement and resupply, to await events. They would defend with honor, but some could see the end. In Canada, on Cape Breton island, the other telling event of 1758 had unfolded. Generals Jeffrey Amherst and James Wolfe besieged and took France's fortified position at Louisbourg in July. The last obstacle to control of the St. Laurence River was removed, and the advance against Quebec was inevitable. It then being late in the year, and with the early Canadian winter looming, there was a pause. Much of the coming year was spent in assembling troops, provisions, artillery and boats for an attack on Quebec, a position that was thought by some officers to be impregnable. James Wolfe disagreed. With determination and cunning, in September, 1759, Wolfe landed a force sufficient to defeat the French outside the fortifications of Quebec. The battle on the "Plains of Abraham" was hardly major in scope, and is often more remembered as the site of the deaths of both commanding generals, Wolfe and Montcalm, but there have been few events more stunning in their consequences. France was finished in Canada, and the last French position, at Montreal, was surrendered by their governor-general in 1760. The only rival to British hegemony in North America had been eliminated. Spain remained, but was directed toward South America and Mexico, and would not be up to the financial burden of contesting British strength. Within the next 15 years, amid disputes over taxation, political rights and Britain's mishandling of her rich colonial territories on the continent, Britain's rival for North America would become her own dependencies. The result would be a civil war among Englishmen to validate what already existed - that the American colonists could (and for 150 years had done) rule themselves and conduct their own affairs. The Great War for Empire in North America, a side show of the Seven Years War, had profound consequences. Britain's greatest adversary had been vanquished; an empire had been won, not only in the Americas and West Indies, but also in influence in India, and the beginnings of a new nation had been created. This was a nation that in the beginning was as English in New York as it was in London, as maritime in Boston as it was in Plymouth, and characterized by similarity of culture, language and common law. In some sense, the North American empire of Britain still exists, and is stronger than ever. Sources for the article on War for Empire in North America:

Anderson, Fred. The Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York, 2000.

Parker, King L. Anglo-American Wilderness Campaigning, 1754-1764: Logistical and Tactical developments. Unpub PhD Columbia U. 1970.

Ward, Matthew C. Breaking the Backcountry: The Seven Years War in Virginia and Pennsylvania, 1754-1765. Pittsburgh, 2003.

|