The Players

The First Afghan War is one of the great anomalies of history. It was a war that defied the law my of enemy’s enemy.

The British

Britain had long since stopped regarding France as the major threat to the Empire. Over the last century Russia had doubled in size to the amazement of all Europe. However the Russian advance hadn’t slowed and now was closing towards India. Britain rightly feared the Russian’s wanted to capture all central Asia and saw destabilising British India as the best way to achieve it. Britain’s main fear was Russia establishing itself south of the Hindu Kush, the mountain range just north of Kabul. While beyond the mountains any army invading India would have to march across a logistical nightmare. But if Afghanistan was captured the Russians could build up a force and march onto the plains of India with little hindrance.

The Afghans

Afghanistan was weak and disunited, ruined by a civil war but under tight control of a competent leader, the usurper Dost Muhammad Khan. Afghanistan was still divided though and many tribes disliked Dost Muhammad Khan’s heavy handed rule. To the east its old enemy Persia, a Russian puppet prepared to cross its borders. To the north Russia was advancing with alarming speed annexing all to her south and already under Russian intrigue the tribes of Turkestan. To the West lay Britain, enemies with both Russia and Persia and becoming increasing alarmed at the Russian advance.

So what stopped these two countries, Britain and Afghanistan, with the same enemies becoming allies?

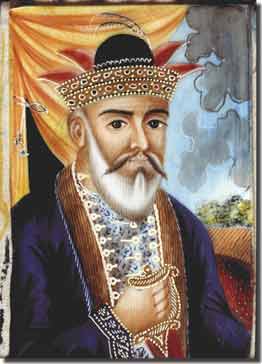

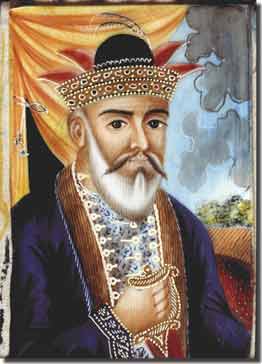

Maharaja Rangit Singh Amir Dost Muhammad Khan

The Sikh Empire of the Punjab

The answer is one man, Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The aging warlord had carved out a small empire mostly from Afghan territory and was an avowed hater of Afghans. Not only that, he had built the most powerful army in the world outside of Europe, the Khalsa, a brotherhood of warrior saints. Trained by European mercenaries, equipped better than most European armies, an artillery park even the British Army in India envied and the finest cavalry in the world. Ranjit was not only a warrior he was a canny diplomat too. He had not just allied himself with the British but befriended them, a test of how much they trusted him is that Britain didn’t even defend her border with him. Just prior to the Afghan war Ranjit had also annoyed Dost Muhammad Khan by attempting to put Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah back on the throne of Afghanistan and by invading and annexing Peshawar the richest province in Afghanistan. It was this Sikh capture of the Peshawar that was to be the cause of the First Afghan War forcing Britain to choose between powerful friend and weak but desirable ally.

Alexander Burnes

The Great Game

Afghanistan until the 1830‘s was of little interest to the British Empire, a huge wild uncharted expanse of hostile tribes, almost as large as India itself and stretching from the inhospitable Sind Desert to the equally barren Turkistan, landwise of little worth. So disunited, it’s Amirs had exercised so little control over the country, that dealing individually with the few border tribes proved a more fruitful policy.

Even during the civil strife which saw Saddozai dynasty deposed by Dost Muhammad Khan who declared himself Amir, the British Empire did little more than offer the deposed Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah exile in a modest house and a small pension.

Afghanistan’s anonymity couldn’t last though. With the Russians marching south and the British west, Afghanistan soon became the centre of both empires imperial policy. For both empires Afghanistan was rather an unattractive proposition to invade, with little unity, an unforgiving landscape and history of bandits, brigands, rebels and religious fanatics.

Britain’s tactics against Russia was typical of the empire, one of trade war rather than military. The opening of a cheap land route for goods through Afghanistan into Persia to undercut Russian goods. Between 1830-7 the talented, womanising and native speaking Lieutenant Alexander ‘Bhokara’ Burnes was sent on series of expeditions back and forth visiting both Dost Muhammad Khan, Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah and Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Punjab.

Burnes was unimpressed by the deposed Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah whom he regarded lethargic and saw little advantage in giving him his requested aid restoring him to the throne. Though in his meeting Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah did promised him free passage across the country if the British did ever restore him. Dost Muhammad Khan from his first meeting Burnes recognised as an astute leader and the man Britain would have to deal with if they wanted a treaty with Afghanistan.

In his report in Bombay of 1833 Burnes delivered to the British governor alarming news. Having surveyed much of the north of Afghanistan he concluded that the was little possibility of Russia invading Afghanistan through Turkestan because the desolate terrain and mountainous barrier would make it virtually impossible. Instead if the Russians were to come it would be much closer to home, via the Kashmir where less resistance would be met and supplies plentiful. Bringing Russia between the three great powers of the region, the Sikh Punjab, British Indian and Afghanistan. Both the Sikhs and the British sure to oppose her.

It dawned on the British that if this were ever to happen Afghanistan would not be the kow-towed country they first thought, in the position of needing security against imminent Russian expansionism but a country to be courted by Russia to aid and supply her if she ever moved on the Kashmir.

Later that year, Dost Muhammad Khan was putting down an attempted rebellion by supporters of Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah, Ranjit Singh invaded Peshawar, the richest province in Afghanistan and added it to his Sikh Kingdom. Meanwhile the Russians encouraged Shah Mohammed of Persia to invade Afghanistan through Herat. Afghanistan was getting ever more unstable.

When talks were arranged in Kabul 1837 Burnes found himself in the unenviable position of competing with the Tsar’s diplomatic mission to win over Dost Muhammad Khan with very little to offer him. Burnes’s offer was protection from Persia and the Russians, but with the Tsar’s representative there offering peace, Burnes really had no position. Matters got even worse when Dost Muhammad Khan told the delegates what he wanted, Peshawar, and military aid for all out war with Ranjit Singh’s Punjab to recover it.

The situation quickly dissolved into disaster for the British delegation when the Russians agreed to all Dost Muhammad Khan’s requests. With the prospect of all central Asia from Persia to Afghanistan falling under Russian control, imminent war between Afghanistan and the Punjab removing the main resistance to a Russian expansion into the Kashmir leaving Russia an easy base to burst onto the plains of Hindustan at a moments notice. The British delegation headed back to India dejected.

Back in India it became clear Britain would have to take an aggressive course of action to avert a potential catastrophe, Dost Muhammad Khan would have to be deposed and Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah restored to the throne.

The diplomat Sir William MacNaughtan was given control of the operation. In 1838 he visited the Punjab, Ranjit Singh gave him assurance of aid in the invasion, but refused to commit troops for the occupation.

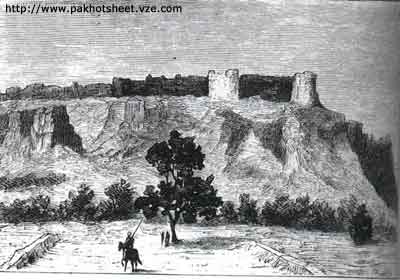

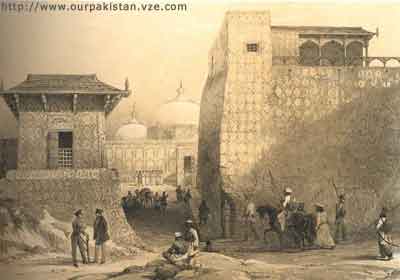

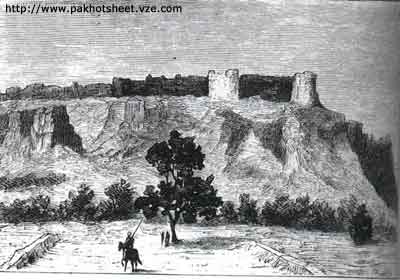

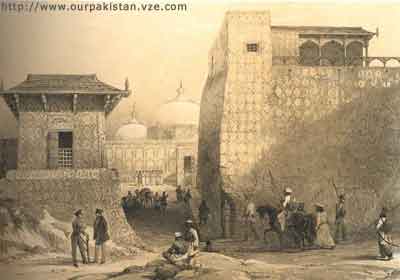

River Indus, Attock Punjab,1839

Bayonets and Breasts

In November 1838 the forces of the Tripartite began to assemble around the camp of Ferozepore near the Setluj river in east Punjab. The customary diplomatic protocols that accompany such an alliance also ensued as the various leaders and dignitaries from the allies attended parades, inspections and passed on official good will. When complete Ranjit Singh invited the commanders of the expedition and some leading men and women from high society including George Eden, Lord Auckland, Governor-General of India over to his place and there treated them to some Punjabi style debauchery. Ranjit organised a raucous drinking session all the time attended to by his harem of finely dressed young boys and several dozen nude dancing girls who would frequently ride horse races for the guests to bet on.

The meeting also gave the leaders the chance to put the final seal on the plan. The march from Peshawar to Kabul through the Khyber Pass is less than 300km, however Ranjit Singh was reluctant to have a British Army march across the Punjab and Lord Auckland far too timid to push the case with him. So instead for the British force and the army of Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah it was agreed would cross the Indian border at the Sind and march over 2,000km to Kabul.

There wasn’t entirely madness in this decision. Britain’s important trade route to Karachi had long been subject to the volatility of the Sind. Long part of Afghanistan before falling to the Moguls a century before the current rulers of the Sind had resumed more than a passing ties with the Afghans and given clear signals they would side with the Afghans. A detour to conquer and occupy the Sind would give the British chance to secure the Karachi trade route and make sure they didn’t have an enemy at their rear.

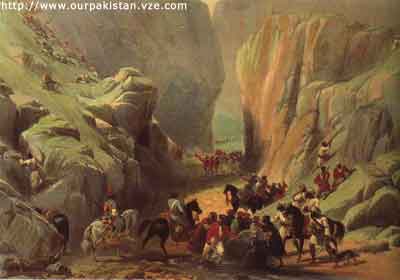

Another perceived advantage of this strategy is that the Afghans would presume the British would enter via the Khyber Pass and mount a heavy defence of this substantial defensive position, by crossing at such a far away pass they hoped to take the Afghans by surprise.

The plan was three forces would enter Afghanistan from different places. The Sikh forces would enter through the Khyber Pass along with a small British contingent lead by Lieutenant Claude Wade.

The British army was divided in two contingents, the main commanded by Sir Willoughby Cotton, 9,500 strong, which had marched from Bengal to Ferozepore and was joined by 6,000 British equipped troops of Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah. Together they would board barges and travel down first the Setluj then the Indus on an 800km ride then invade the Sind, march to Quetta and on through the Bolan Pass.

Meanwhile a Bombay force 5,600 strong under Sir John Keane, who was in overall command of the Army of the Indus, was sailing direct from Bombay to Karachi and would rendezvous with the rest of the army in Quetta.

With the army would go a train of, 30,000 camels, 8,000 Ox carts, 40,000 camp followers consisting of families, servants, animal handlers and prostitutes. 60 camels alone carried the personal effects of one brigadier, he also took 40 servants. Most officers brought half a dozen servants of their own, packed silver plates to eat from, fine wine chest and bathtub. Two camels carried nothing but cigars for the officer’s mess and the 16th lancers brought a pack foxhounds

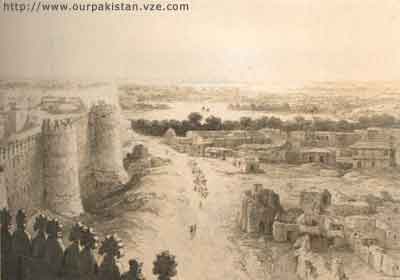

The Sind, Thatta, 1839 & 1840

Ancient Sehwan, The Sind, 1839 Modern Sehwan, The Sind, 1844

First Shots

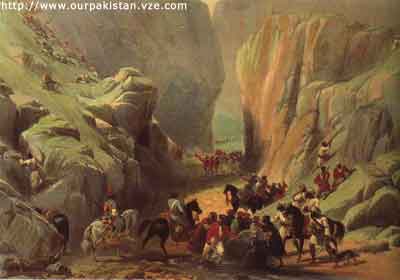

The war was started not by a shot but a bribe, as the wild Gilzai tribe who controlled the passes between India and Afghanistan, were bought off by a promise of 8,000 rupees a year to keep them open for the British.

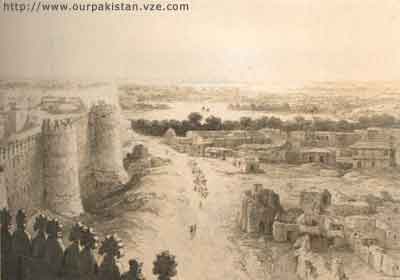

On 10th December 1839 the Bengal contingent of the Army of the Indus along with the men of Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah boarded boats and began their long journey to Kabul. The army followed the Indus through the Sind to North of Hyderabad and then began the dirty business of conquest leaving a trail of burnt and looted villages and countryside behind them. Arriving at Hyderabad the army sacked the capital city and extorted 2½ million rupees tribute from the rulers of the region which would go a long way to paying for the expensive expedition.

Hyderbad 1844

With the Sind now suppressed, a garrison was left and the army marched north east. Ahead lay the most daunting part of the Journey, a month long march through the salty deserts of the upper Sind to Quetta, in midwinter the temperature scorching by day and freezing by night, with not a blade of grass to feed the horses nor camels, not carried on camel back.

Day by day the scenery was so bland that only way to distinguish one day from another was the count of dead camels, commented one officer. Another was by the number of servants deserting their master. The ample provision of stores ensured that officers had all the luxuries to choose from at the table, from brandies, beers, wines, game, mutton and butter, except one, water. Water was running so low it didn’t matter that perhaps as little as ten percent the amount of grain had been packed to feed all the animals, for they were dropping like droves from lack of water long before they starved to death.

Karachi 1840 Road to Quetta

After a couple of weeks it seemed things could hardly get worse, but they did. With inadequate sanitation and hygiene it wasn’t long before dysentery and cholera broke out. Winter gales blew day and night and soon Baluchi raiders began to trail the army ambushing stragglers and raiding the train by night. As the animals died, the food they were carrying lost soon the food situation became desperate for the troops too, the whole army was put on half rations and camp followers left to their own means.

For Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah’s troops and the Bombay column following from Karachi it was even worse as they followed behind the Bengal column through tracks strewn with the rotting and disease ridden corpses of animal, camp follower and soldier alike.

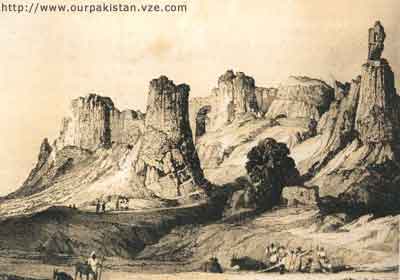

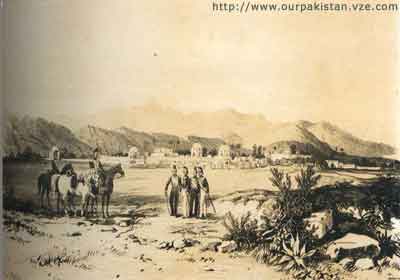

Dadur, entrance to Bolan Pass 1838

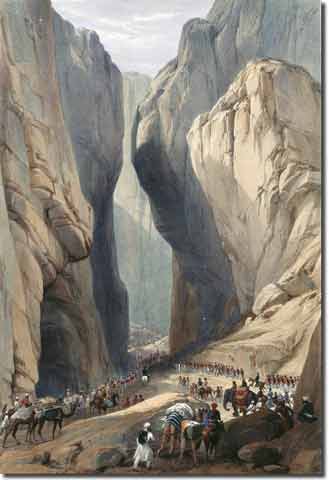

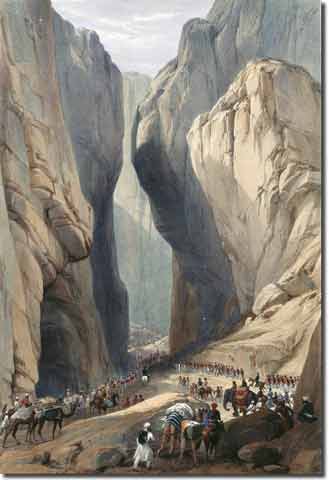

After a month the army arrived at the Bolan Pass and received the first good news for weeks, they had totally outmanoeuvred the Afghans and the Pass was completely undefended. The 100 kilometre long Bolan Pass is 150 metres high and as narrow as 20 metres wide in some places, it would have been a nightmare with even a few Afghans defending it.

Two weeks of marching across the jagged rock and the army exited the pass onto the plain of Shal rejoicing at the first sight of green and the silence of an army marching on soft grasslands instead of shingle. Shortly the famished army arrived at the mud town of Quetta almost immediately exhausting it of both grain and chow. Far from being a saviour, 50 horses were shot at Quetta and 17 more died of exhaustion in a single day.

Bolan Pass

The army recuperated at Quetta for a week then on the 7th April set out across the Kandahar plain and fields of golden wheat and orchards full of apricots, apples, pears, peaches, figs and cherries, but still no water. On the 25th of April with the army spoiling for a fight, the city of Kandahar fell to a Burnes bribe. With doors flung open and garrison long fled Shuja-ul-Mulk Shah retook the throne of Afghanistan in front of pitifully few of the city’s population who could be bothered to watch as he paraded the streets. Three days later he was coroneted before his grumblingly apathetic subjects and then got drunk with his Sikh and British masters.

Bolan

Part Two to be published next issue!

|