Notice: This is the official website of the All Empires History Community (Reg. 10 Feb 2002)

Ming Dynasty Military Attire |

Post Reply

|

| Author | |

Preobrazhenskoe

Consul

Joined: 27-Jul-2006 Location: United States Online Status: Offline Posts: 398 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Topic: Ming Dynasty Military Attire Topic: Ming Dynasty Military AttirePosted: 14-Aug-2006 at 19:19 |

|

(Note, I posted this same thread in SMQ Forum Website, under the name PericlesofAthens) Recently, in another thread I've started in the Early Modern Age Forum entitled Spanish Armada vs. the Ming Treasure Fleet, found here at http://www.simaqianstudio.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=7318, a member there at SMQ, the glorious and beloved Byzantine Emperor (yes, you should bow to him, lol

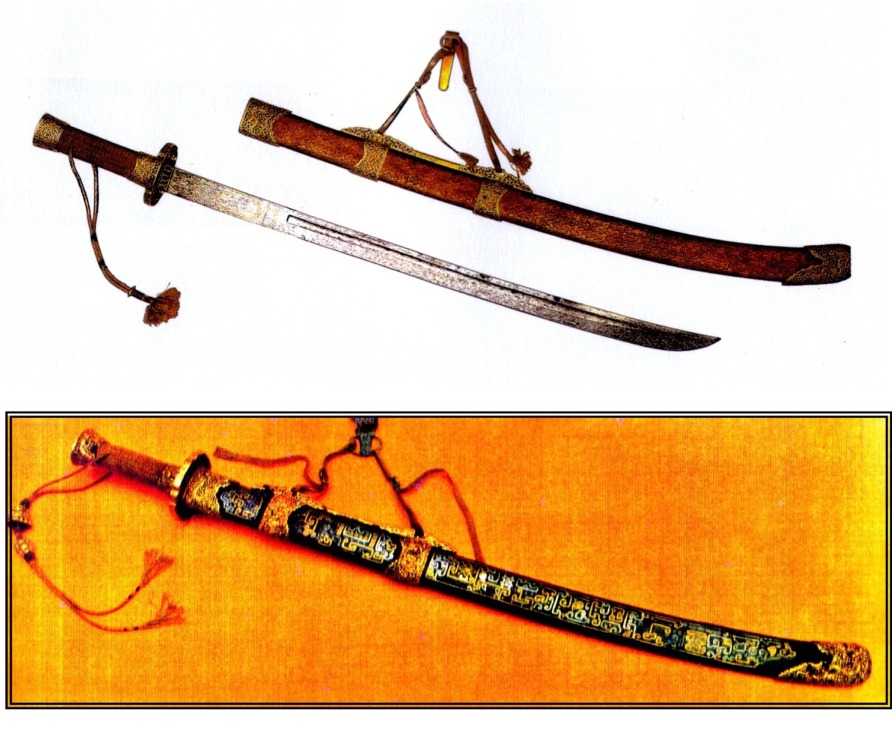

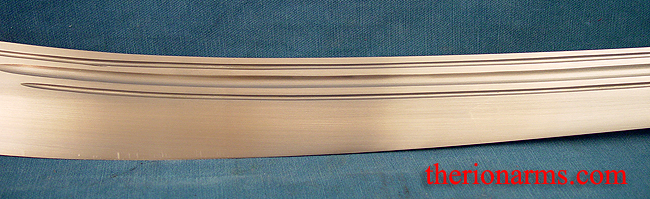

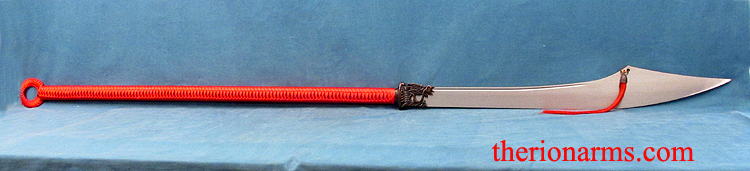

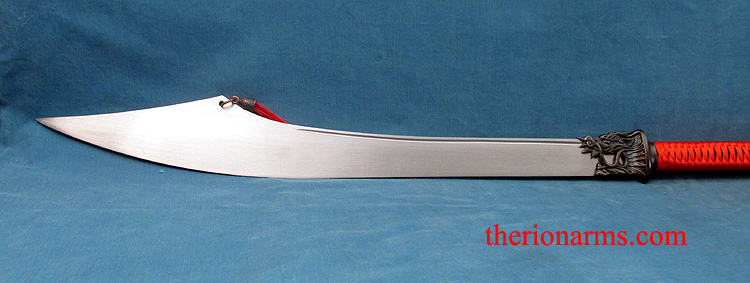

First, let's start with weaponry, specifically-speaking, swords. During the Ming Dynasty, the sword type known as the pei dao began to become more widespread and used in more popular fashion amongst military units than other Chinese sword types, most notably the jian (generic term for a double-edged Chinese sword, most often used by Chinese nobility). The pei dao had evolved from the ancient Chinese dao, which could refer to any number of swords (or even domestic knives) in the style of a single-edged blade meant for slashing and chopping. Although the jian and some types of daos are more straight in appearance (like a European broadsword), the single-edged blade of the pei dao was more saber-like, used first by the Central Asian Turks who used the saber-style sword since at least the 8th century AD, adopted by the Mongols of the Chinese Yuan Dynasty (1279 -1368 AD), and then continued in practice towards the Chinese reestablishment of control during the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644). The style of the curved, single-edged blade for swords spread to other peoples as well, only with different names, for example, the Persian Shamshir, the Indian tulwar, the Afghani pulwar, the Turkish kilij, the Arabian saif, the Mameluke scimitar, and of course the European saber and cutlass. According to wiki, the four types of pei dao swords are thus: *yanmao dao, or "goose-quill saber." This weapon, similar to the earlier zhibei dao, is largely straight, with a curve appearing at the center of percussion near the blade's tip. This allows for thrusting attacks and overall handling similar to that of the jian, while still preserving much of the dao's strengths in cutting and slashing.   *liuye dao, the "willow leaf saber." The most common form of Chinese saber, this weapon features a moderate curve along the length of the blade. This reduces thrusting ability (though it is still fairly effective at same) while increasing the power of cuts and slashes. This weapon became the standard sidearm for both cavalry and infantry, and is the sort of saber originally used by many schools of martial arts. Perhaps due to that same popularity the name "willow leaf saber" has now become somewhat generic, and is sometimes applied to other forms of dao (such as the niuwei dao, below).   *pian dao, "slashing saber." A deeply curved dao meant for slashing and draw-cutting, this weapon bears a strong resemblance to the shamshir and scimitar. A fairly uncommon weapon, it was generally used by skirmishers in conjunction with a shield. .jpg) *niuweidao, the "oxtail saber." A heavy bladed weapon with a characteristic flaring tip, this is the archetypal "Chinese broadsword" of kung fu movies today. It is first recorded in the early 1800s (the late Qing dynasty) and only as a civilian weapon; there is no record of it being issued to troops, and it does not appear in any listing of official weaponry. Its appearance in movies and modern literature is thus often anachronistic, and it is also sometimes mislabeled as a willow-leaf saber.  These swords of course, can be adapted to the Chinse weapon known as the guan dao, or pole-sword and polearm in English, as examplified here...     Other names for the guan dao sword are the formal Chinese title of yanyue dao (meaning Reclining Moon Blade in Chinese), or it's Japanese version, the naginata. Now that I've introduced this thread with a bit of history on Chinese swords and the types of swords common during the Ming period, let's look at some Ming Dynasty types of armor worn by common infantry, cavalry, naval marines, and military officers, shall we?

Before delving into the good stuff (pictures), I'll display a brief history and run down of Chinese armor before the Ming period (1368 - 1644), taken from wikipedia.org (which, keep in mind, isn't always the best place on the web for referencing Chinese history). Taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_armor, which briefly describes Chinese armor and warfare starting from roughly the 17th century BC, and cutting off at around the 5th century AD... Ancient armour Most armour of ancient China was made of leather and animal hide, but later bronze and iron were used. One of the early armours that were used, was from Shang: early Shang nobles wore breastplates, that were made from pieces of shell tied together. The bulk of the army had little more than shields, made of leather with a bamboo frame. Bronze helmets were used and were highly decorated. After the defeat of the Shang, the Zhou used many weapons and types of equipment that originally came from the Shang. However, the Zhou incorporated some of their own different or unique styles of armour. One type was the kia, a sleeveless coat of animal hide formed on a wooden dummy. The hide used was of buffalo and rhinoceros, buffalo was more often used later on, because of the disappearing of rhinoceros in the region. Another armour used by the Zhou was the kiai, a boiled leather on a fabric backing. The Zhou helmet -- like the Shang - was made of bronze, but less decorated. Chariots were used extensively during the Spring and Autumn Period. The chariots were mainly used as a shock weapon and a platform for archer; but chariots were restricted to flat terrain and when used against well organized infantry, it was often defeated. Shang chariot was often drawn by two horses, but four are occasionally found in burials. The crew of the chariot consisted of an archer, a driver, and sometimes a third armed with a spear or dagger-axe. Chariot use declined during the Warring States Period, probably because of the introduction of crossbow and cavalry. Zhou chariots were protected by leather, and sometimes came with a canopy to protect the crew, but this was probably removed before going into battle. Chariot horses were protected by animal skins -- most popular was tiger skin. The production of weapons was, in most states, control by central government. The most popular weapon of the time was the sword. For this reason, most armour was made to protect against slashing attack. Spears, dagger-axes and many other weapons were used, but were consider inferior to the sword in close combat. Another weapon that was used was the crossbow, which had a range of 600 paces. To counteract this, shields were used to counter the threat of the crossbow. The shields were mostly made of leather and wood, and varied in sizes. The metal that was used most for military purpose was bronze.During the Warring States Era, most armour was made of leather or bronze, or combination of both. Wrought iron (God I hate wikipedia sometimes, they got this completely wrong, I'll explain why below) begun to appear in the 5th century BC, but didn�t begin to replace bronze until the 2nd century BC. Qin have a reputation for having superior weapons and armours, when compared to the other states. It is believed that Qin was the first states to mass-produce iron weapons and armours, which contributed to their victory against their rival states. Most of the Warring States maintained large armies, numbering anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000. With such a large number of men, it became prohibitive to give all of them armor. Armour was most common for elite soldiers. The armour usually wore by these soldiers consisted of a lamellar cuirass and helmet. The lamellar cuirass wore by these men was made of hundreds of small overlapped metal or leather plates laced together to make a flexible and light protection. Some terracotta warriors wear no armour; it is suggested that these were skirmishers or support troops for the chariots. Of the terracotta warriors thus uncovered, Pit 1 shows approximately 61 percent of the soldiers wearing armour, Pit 2 over 90 percent, and pit 3, being in a command compound, 100 percent. Unarmored warriors tend to be placed at the front of these terracotta formations. Traces of paint that were found on Qin terracotta warriors suggesting that the Qin colored their armour black. The terracotta warriors also showed a wide variety of armour used by the Qin, which included leather and bronze. Examples of armour from the ancient China are rare. Qin Shi Huang ordered weapons, and probably armour too, to be burnt. That might be the reason for so few extant examples of ancient armour. Medieval Armour Chinese armour developments in medieval times began with the fall of the Qin dynasty in 207 BC and the rise of the Han Dynasty in 202 BC. The early Han army numbered possibly in the hundreds of thousands, so armour was standardized to meet the need. One of the armours used by the Han was the liang-tang, or "double-faced armour", a lamellar cuirass usually made of leather, but which could also be made from metal, which was worn over the shoulder with a strap. This armour was used by both the infantry and the cavalry. A much heavier and expensive version, consisted of iron plates laced together, was worn by officers. The infantry were armed with a great variety of weapons, which included sword, spear, halberd, and crossbow. The cavalry were similarly armed, but used smaller crossbows compared to the infantry, which could be used mounted. Shields continued to be used, mostly made of wood or metal. Some sources suggest that the Han placed infantrymen with large heavy shields in front, while crossbowmen and archers were deployed behind them. As they marched, the front ranks repelled attacks, as the rear constantly showered the enemy, but this formation must have been rare. Armour for horses began to appear around the end of the Han dynasty, but the earliest armour found dates back to 302 AD. Full armour for cavalry appeared during the 4th century AD. During the Three Kingdoms Period, fully armoured cavalry were extensively used for shock. Early horse armour came in one piece, but later armour came in multiple pieces: chanfron (head protector), neck, chest, and shoulder guards, flank pieces and crupper. Most cavalry served as mounted archers, and sometimes remove their arm protection to used their bows or crossbows. By the time of the Han, the primary metal used was iron. But bronze weapons and armour continued to be used for some time. There's but one thing that really bothers me about this wiki article, and that needs to be fixed. Early Chinese iron of the Zhou and Warring States period was never wrought iron, an iron obtained by the bloomery technique which was a practice used elsewhere in the world during the death of the Bronze Age and the initiation of the Iron Age. The death of the Chinese Bronze Age came in the 6th century BC (same century when Confucius lived) when cast iron was innovated by the Chinese discovery of the blast furnace, which reached temperatures higher than 1130 degrees celsius in order to melt iron ore into a liquid to be casted-and-molded into any shape without laborious beating and collecting of the bloom sponge found in wrought iron, thus the name cast iron should be used here. Wrought iron was not found until the Han Dynasty, when the Chinese figured out how to puddle molten pig iron and reduce it's carbon content. However, they also figured out how to melt wrought iron and brittle, over-carburized cast iron together to form an iron-alloy intermediary: essentially, steel. Anyways, moving onto explaining lamellar armor and its use elsewhere...  Picture of a Qin era (221-207 BC) kneeling crossbowman, just one of 8,099 Terracotta figures of the Terracotta Army built and assembled by Qin Shihuangdi (the First Emperor of Qin), and placed in his tomb by 210 BC. His armor is of the lamellar-type, small plates of armor fitted together to make an armored vest around the chest and upper-arms. Taken from lamellar armor article in wiki... Lamellar armour is a kind of personal armour consisting of small rectangular plates (lames) which are laced together in parallel rows. Lamellar armour evolved from scale armour. It is made from pieces of lacquered leather, iron, steel or horn held together with silk, leather, or cotton thread. When the lames are made up of leather one would often water harden it or impregnate it with wax in a process called cuir bouilli. Various materials have been used throughout the ages across many cultures, with different techniques of construction and designs of coverage. A common technique was approximately 30% animal fat mixed with 70% candle wax stirred until blended, applied with a brush and allowed to cool, afterwards excess was scraped off and readded to the next batch. Lamellar was an armour that, when made out of materials such as leather, facillitated a high mobility for a comparably high level of protection. Lamellar was often worn as augmentation to existing armours, such as over a maille hauberk. The lamellar cuirass was especially popular with the Rus, the Scandinavian settlers of Russia, as it was simple to create and maintain. Lamellar is pictured in many historical sources on Byzantine warriors, especially heavy cavalry. It is thought that it was worn to create a more deflective surface to the rider's armour, thus allowing blades to skim over, rather than strike and pierce. Developed by the Assyrians circa 900�600 BC, the style was used up through the 16th century. It is generally associated with the Japanese Samurai, although the armour came to Japan from contact with Tang Dynasty China. It is also associated with the steppe people of southern Russia and Mongolia. Now for the pictures! Hooray! First up, one of many armor styles that was used during the Ming Dynasty was the old Tubo (Tibetan) style of iron-plated, chain-linked, lamellar-flap armor, as demonstrated in this picture below...  This armor retained a non-rusting quality due to silver being smelted into the iron, a style of armor which was originally used during the reign of Tubo bTsan-po Dri-gum-btsan-po, 2 millenniums ago in Tibet. This next picture is from the Ming Tombs in Beijing, and shows great detail from a Tomb Guardian stone statue, shown below. Notice on this stone portrayal of the Tomb Guardian the fish-scale and lamellar leather/iron (or steel) armor covered by silken robes, the adorning helmet and tassel, and metal belt-clasp at the center of his waist in the form of a dragon's head (or is it a lion's head?). He's holding a blunt, battering baton weapon in one hand, while in his left hand he appears to be gripping his sheathed sword by the hilt. Judging by his officer-looking-status, the sword is most likely in the classic, lengthy jian (double-edged-sword) of the nobility. Although the statue representation is a good one, here is a rare picture of a full Chinese armor set, as seen below. ...and a better-looking close-up below this... Here's the examples of the Shan Wen Kia (Mountain Pattern Armor)

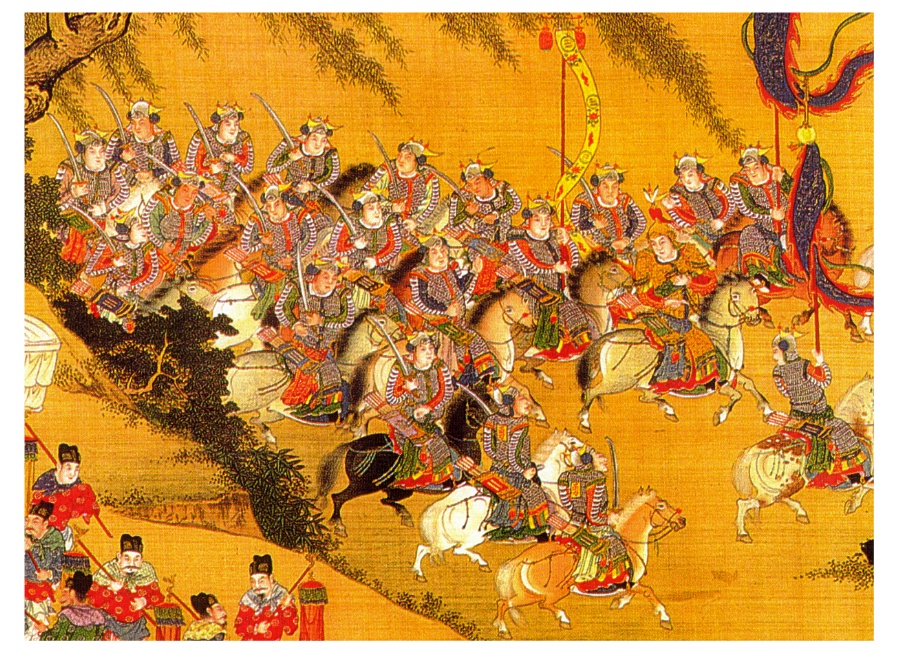

http://www.flatbow.com/shanwenkia/shanpics.html Some Ming Dynasty era (1368 - 1644) Imperial cavalry guards, notice the saber daos they wield in the first picture, as well as the long guan dao (pole-swords) they're weilding in the second picture, along with lamellar-scale, brigandine, and jack-of-plate styles of scale armor...

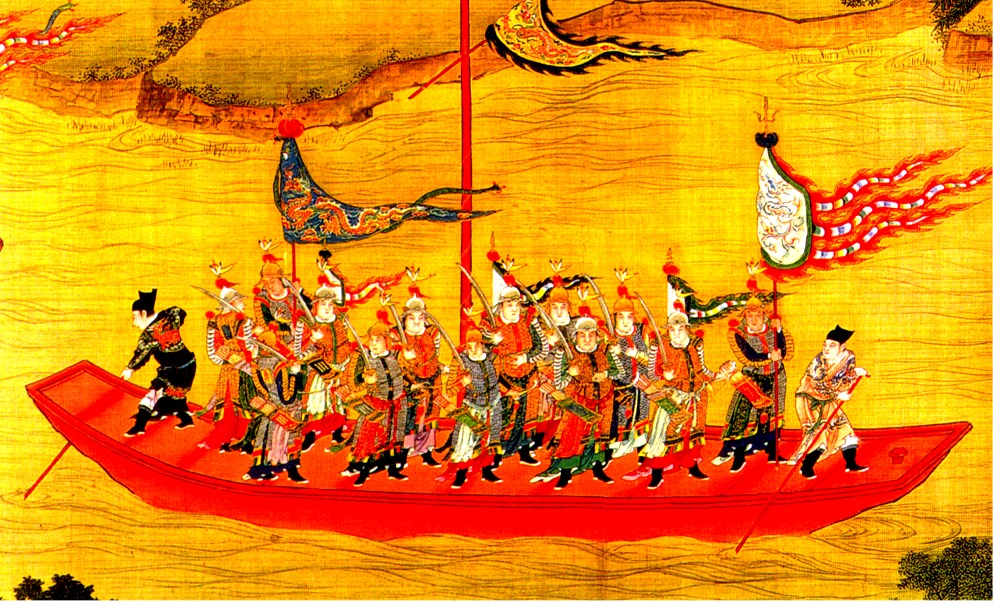

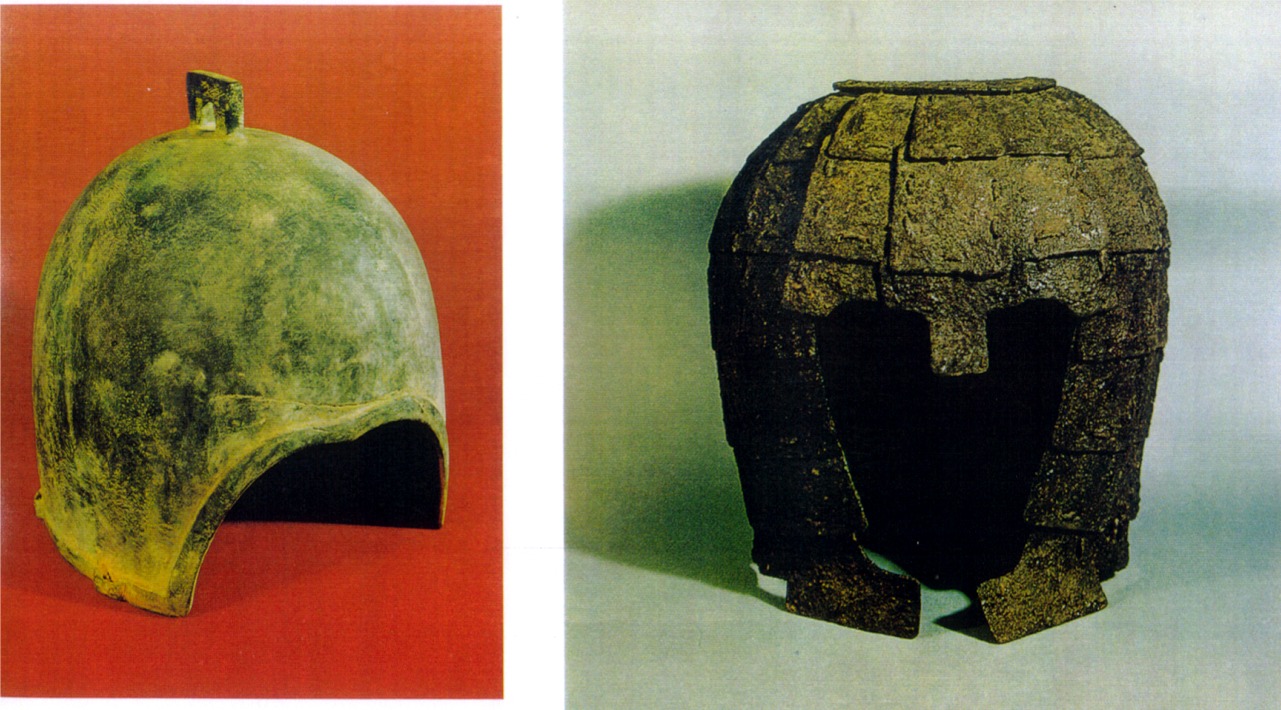

This next pic shows Ming troops being transported by a small river boat...  Hey guys, I'm back, and it's time to look at some helmets. First, I've found a nice precursor to the Chinese Ming era (1368 - 1644 AD), as I've found this pic from http://chinese-armour.freewebspace.com/photo.html, and these Chinese helmets below are actually more than 2,000 years old, since they are dated to the Warring States Period (481 - 221 BC). You can tell by the green rust over a near orangish tint that the first helmet is cast of bronze, while the severe rust and coloration of the plates of the second helmet indicates cast-iron.

Here's a Ming Dynasty helmet below now found in a museum in Japan, as it was used in the Imjin War of the 1590s, where Joseon (Korea) and Ming (China) were allied against a Japanese naval invasion of Korea.  These next pictures are actually from an 18th century Qing Dynasty military uniform, but it shows the brigandine style of armor found in the late Ming period, with the lamellar plates of steel riveted into the suit itself, as well as a picture of the metal helmet used.       Description taken from http://www.denner.ca/weapons/eastern/index.html: Blue silk with heavy silk embroidery. Light steel plates in the shoulder covers, chest and back, secured by light steel rivets. The thighs are covered with narrow light steel plates in three rows which would have been covered in the same blue silk as the rest of the suit. However, the covers are gone. The same armour plates as above are fastened inside as well. The helmet is typical Chinese of the period, plain steel, small visor and plume holder on the top, the neck guards are not present. The edges of the various pieces are frayed where they were bound with black silk. Complete with a temple pole arm, the top piece of which is made of brass nicely engraved, on a black wood staff. Overall, the whole suit is quite spectacular. Glad to be of service,

Eric Edited by Preobrazhenskoe - 14-Aug-2006 at 21:59 |

|

|

|

Preobrazhenskoe

Consul

Joined: 27-Jul-2006 Location: United States Online Status: Offline Posts: 398 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 16:00 Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 16:00 |

|

Ok, now for projectile weapons. Let's start with really old Chinese crossbows, which date back to the Warring States Period (481 - 221 BC) of China.

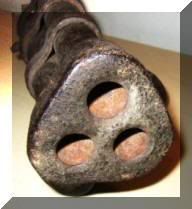

This picture below is of a precursor to the Zhuge Nu (Zhuge's Repeating Crossbow), excavated from a Chu State tomb during the Warring States Period.  This picture below shows a Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) era crossbow, however, it is just the bronze fitting and trigger mechanism, the wood has since decayed and rotted away.  Here is a recreation of the Zhuge Nu mentioned earlier, which dates to the Three Kingdom's Era (220 - 280 AD), apparently invented by the Shu Kingdom Prime Minister Zhuge Liang...  Here's an illustration below of the Zhuge Nu in use; this is actually an old Korean scroll depicting a naval battle of the Imjin War (1592 - 1598 AD), where a Ming ship is attacking a Japanese vessel while employing the Zhuge Nu...  The Zhuge Nu suffered from a lack of accuracy. Fired from the hip, the bolts were fired in sequence from pumping the corking lever forward and backward, arming and releasing in a continuous cyclic process until the magazine was emptied. This rocking action did not allow for precision firing, nor did the inability to sight along the barrel as in a crossbow or a modern gun. The short effective range of the Zhuge Nu also made it useless except for close-quartered fighting. This was where the Zhuge Nu excelled and proved its worth. The short maximum range of approximately 80 meters and effective killing range of only 10-20 meters in comparison to regular contemporary Chinese crossbows, was offset by the rapid rate of fire achievable. Used for concentrated fire, the deployment of the Zhuge Nu was limited in the field, possibly to provide covering fire for an infantry charge or a retreat, or conceivably for the close range fighting required when performing what modern armies now call a "reconnaissance-in-force", to keep the heads of your enemy down in an event of a firefight. However, what the Zhuge Nu lacked in the field, it made up for in a defensive environment. Zhuge Nus used a magazine of between 7-10 metal tipped bolts which could be emptied within 15-20 seconds. This rapid discharge of large quantities of bolts was ideal when used as a defensive weapon as small teams of Zhuge Nu armed soldiers could fill the air in front of a door or window or on top of fortress battlements with lethal bolts when attacked. The bolts used were also often dipped in a fast acting poison to increase its effectiveness, compensating for the relatively low penetration power. In this way, even a simple scratch by a Zhuge Nu bolt could prove lethal. Info taken from http://authors.history-forum.com/liang_jie...ns-zhugenu.html This next pictures are of hand-held Ming-era hand-cannons, the first one here dating to 1368 AD, the beginning reign of the Hongwu Emperor...    The last one is interesting as well, with a triple barrel stock. Here's an illustration of Ming Dynasty soldiers and officers, and if you notice the guy on the right, he's holding a triple-barrel hand-cannon like the one seen above.  Description from http://www.wsbx.com.cn/11/00200/index.htm: In Ming dynasty (1368 -- 1644), there is a kind of fat coat that reaches to knees, close-fitting sleeves and cotton inside, the color is red, it is just for ride. Common soldier wears hauberk, wears iron-net skirt and trousers under waist, and iron-net shoes. If you guys liked those pictures of military parade I posted earlier, here's another one in a fuller view of what's going on...  Eric |

|

|

|

Gubook Janggoon

Sultan

Retired Global Moderator Joined: 08-Aug-2004 Online Status: Offline Posts: 2187 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 19:51 Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 19:51 |

Just a detail pick here, but from what I understand this is actually a Japanese piece depicting Korean sailors. I could be wrong though, I'll have to look into a bit more, but the style is very Japanese. Great post though. :] Edited by Gubook Janggoon - 15-Aug-2006 at 19:53 |

|

|

|

Omnipotence

Baron

Joined: 16-Nov-2004 Online Status: Offline Posts: 494 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 22:39 Posted: 15-Aug-2006 at 22:39 |

|

Are you sure the top two cannons are hand held cannons instead of just cannons? Or is that just a blown up picture?

|

|

|

|

Genghis_Kan

Knight

Joined: 01-Dec-2005 Online Status: Offline Posts: 58 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 16-Aug-2006 at 10:17 Posted: 16-Aug-2006 at 10:17 |

|

The development of cannons betweeen Europe and China is actually quite different. The original cannons in China is usually small and the one in Europe areusually big. The funny thing is that the EUropean wanted smaller cannons while the CHinese wanted bigger cannons.

|

|

|

|

Preobrazhenskoe

Consul

Joined: 27-Jul-2006 Location: United States Online Status: Offline Posts: 398 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 16-Aug-2006 at 11:20 Posted: 16-Aug-2006 at 11:20 |

|

|

Killabee

Earl

Joined: 01-Feb-2006 Online Status: Offline Posts: 269 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 17-Aug-2006 at 13:57 Posted: 17-Aug-2006 at 13:57 |

|

Miao Dao - Distant Cousin of Katana, is said to be invented by Ming General Qi Ji Kuang during the time when China was heavily under the raid of Japanese pirate . Whilst facing the ferociuos Japanese private, Qi incorporated the idea of Katana into the new weapon named after General Qi, Qi Jia Dao. The current Miao Dao is the direct descendant of Qi Jia Dao.

|

|

|

|

Preobrazhenskoe

Consul

Joined: 27-Jul-2006 Location: United States Online Status: Offline Posts: 398 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 18-Aug-2006 at 16:39 Posted: 18-Aug-2006 at 16:39 |

|

Thanks for the info killabee, good stuff.

For info on the Ming Dynasty military and soldiers, this excerpt is taken from CHF, http://www.chinahistoryforum.com/index.php...topic=9217&st=0

Military system Under the Ming, military service became hereditary. A soldier and his family would be registered as a military household. Each of these military household's had an obligation to produce a young man to serve in the army. The hereditary system in it's early years had guard units numbering 5,000 men, further divided into battalions of 1,000 and companies of 100. Later, the number of soldiers in a guard unit was increased to 5,600 men, comprising of five battalions of 1,120 men, with each battallion divided into companies of 112 men. In total, the Ming army in the late 14th century numbered approximately 1.2 million hereditary soldiers. During the reign of Yongle (Zhu Di) three training camps were established, which troops were sent to in rotation. The first specialised in infantry warfare, the second in cavalry warfare and the third in artillery. While this worked very well at first, it stagnated after 1435 and had to be revived in 1464 by the Chenghua emperor. I will cover the infantry, cavalry and artillery of the early Ming army individually. Infantry The standard company numbered 100 men in the years before Zhu Yuanzhang established the Ming in 1368. Each 100 man squad consisted of 40 spearmen, 30 archers, 20 swordsmen and 10 men operating firearms. Later, the army was reorganised and the standard company increased in number to 112 men, though they were likely similarly equipped. These soldiers undertook a sophisticated training program, whereby infantry were well trained for maneuvering around the battlefield and performing specific drills in the heat of combat, much like the training system of the European renaissance. Chinese armies of the Ming period used a wide variety of spears. All were generally quite long and tipped with a socketed, tapered steel blade. Some types had downward curving hooks projecting from the blade that were designed for dismounting horsemen. Tridents and more exotic designs existed, but it is doubtful that they were used in large numbers in the army. Ming archers were armed with long composite bows and various types of arrows, including specialised designs tipped with deadly poison .The most interesting of these designs was the rocket arrow. The rocket arrow was said to have great range and power, piercing through iron breastplates and hardwood planks. But was apparently almost impossible to aim with, for this reason rocket-arrows were usually released in massive swarms. This greatly demoralised the enemy as they would be unable to predict the point of impact. Crossbows were also used in large numbers and probably employed in much the same way as during the preceding Yuan and Song dynasties. Chinese swords of the Ming period had their origins in central Asian sabres. Ming infantry swordsmen usually carried a goose-quill or willow leaf sabre. The former being comparitively straighter and more suitable for thrusting than the latter, which had a deep curve and was primarily a slashing weapon. Sabres were often used in combination with a shield by special fighting squads. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Chinese firearm technology was the most advanced in the world. The most widely used gun weighed roughly 5lbs and was attached to a long wooden stock which was tucked under the arm or placed over the shoulder before discharging. Ammunition came in the form of both arrows and solid balls. During Yongle's second campaign in Mongolia, a Chinese army used arrow-firing guns to smash the Mongol cavalry in battle. In his fifth campaign, the emperor ordered his men to first attack with firearms and then to follow up with bows and crossbows--indicating these early guns must have been reasonably effective. Indeed, firearms were instrumental in the Ming conquest of Dai Viet, and proved decisive in a number of battles. However, for the most part it was artillery--not handheld firearms, which gave early Ming armies an edge. Cavalry Cavalry were a minority in the Ming military. However, they were still an essential component of Chinese armies. Yongle once said "Horses are the most important thing to a country.", while he may have been exaggerating, it's clear that the cavalry was highly valued. Ming cavalry were divided into two types--lancers and mounted archers. The former were equipped with helmet, armour and sabre, as well as a long spear and round shield. The latter were also armoured and carried a sabre, but the primary weapon of a horse archer was his composite bow. Lancers typically charged after the enemy had been softened up with missile weapons, as they proved unable to face spear-armed infantry and artillery bombardment directly. Whereas horse-archers were often the first into battle, meeting the enemy with arrows before the rest of the army engaged in hand to hand combat. Time and time again, Chinese horsemen proved their worth on the battlefield, though generally when fighting nomads they needed support from infantry. In 1365 Li Weizhong of the Ming defeated a Wu army with a cavalry charge which he led in person. Later, Zhu Di's succes against both imperial forces and Mongol nomads was due in no small part to his strong cavalry. In 1422 Zhu Di led 20,000 elite cavalry and infantry into Manchuria and won a string of victories over the eastern Mongols. In the later stages of the dynasty. Chinese cavalry severely declined and proved unable to stand up to nomads. Qi Jiguang had to develop specific tactics to ensure success when fighting on the northern border. His armies were infantry and dragoon based, using wagon laagers mounted with light cannon to protect against cavalry charges. This proved succesful--the Mongols sued for peace with the Ming soon after Qi Jiguang was put in charge of the border defence. Artillery Chinese armies of the Ming period made wide use of artillery. Both on the field as well as for the siege and defence of fortifications. It would seem almost every military expedition had a substantial artillery train. This undoubtedly contributed to the success of early Ming armies against Mongol nomads and rivals. Chinese cannons were cast with both bronze and iron. Ammuntion came in the form of stone, iron and lead balls, or large steel-tipped "arrows" with leather fins. Grapeshot was also widely used. Early Ming cannons usually have thickened walls around the explosion chamber, as well as reinforcing rings cast along the length of the barrel. Weight and calibre vary widely, though Chinese cannons seem to have been much smaller than European bombards. Firearms were produced in very large numbers, from 1380 onwards 1000 bronze cannons were manufactured a year, in 1465 alone 300 very large artillery pieces were manufactured. And in 1537 soldiers in Shanxi were supplied with 3000 brass cannon. In the late 14th century, each warship was armed with 4 cannons, 20 fire lances, 16 handguns, and large numbers of grenades and fire arrows. Several field pieces are illustrated in Ming sources. From 1350 onwards, one of the most popular designs was the "long range awe-inspiring cannon", this weighed in at 160lbs and could fire a 2lb lead ball hundreds of paces, grapeshot came in the form of 100 small pellets held inside the same bag. A more interesting type is the "Crouching Tiger Cannon", a small bombard weighing 47lbs and carried on the shoulder, it had two "legs" for elevation and was stapled onto the ground with iron pins before firing. these designs continually advanced over the next few hundred years, and indeed the latter remained in use until the 18th century. Many other artillery pieces existed, but we need not cover them here. Artillery seems to have performed well when it was used. In Yongle's Mongolian campaign of 1414, the Ming army arrayed cannons in front of cavalry units and obliterated a Mongol cavalry charge, killing "countless" Mongols and terrifying the enemy horses. In the conquest of Annam, the Chinese used artillery to great effect in the field, on water, and in sieges. Though effective in the field, early artillery was probably more effective in the defence and siege of fortifications. In 1412 Yongle ordered the stationing of five cannons at each of the frontier passes. Gunpowder weapons had almost completely replaced trebuchets in sieges. During the siege of Suzhou in 1366, large earth platforms were built and "bronze general" cannons placed on top of them to batter the walls, trebuchets were used to launch diseased corpses into the city rather than attacking the walls directly, and thousands of rocket-arrows were fired to set Suzhou alight. Conan the Destroyer from CHF also listed these as the primary sources for this info... Science and Civilization in China: Missiles and Sieges--Joseph Needham Science and Civilization in China: The Gunpowder Epic--Joseph Needham War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China--Peter Lorge Firearms: A Global History to 1700--Kenneth Chase Weapons in Ancient China--Yang Hong Chinese Ways in Warfare--Kierman The Cambridge History of China: Ming Dynasty 1368-1644--Frederick W. Mote 1587: A Year of No Significance--Ray Huang Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle--S.H. Tsai The Glory and Fall of the Ming Dynasty--Albert Chan Also, I'd like to talk about Chinese metallurgy during earlier periods that were refined long before the Ming.

One point to make about their early ability with creating blast furnaces is that when China first started to refine iron ore into iron products at this stage (effectively phasing out the Bronze Age, a process from the 6th century BC until the 1st century BC), the early blast furnaces were able to melt and liquidate iron which could be cast into fairly brittle iron parts that had a carbon content that was considered too high to be steel (over 3% carbon throughout the iron mixture). It wasn't until the processes of decarburization and quench-hardening (rapid-cooling) that Chinese iron (and fairly brittle, quench-hardened steel, like the ancient Greeks often used) was improved that iron became significant in warfare, not just agriculture, by the late Warring States Period in the mid 3rd century BC. By the Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD), the Chinese had figured out that mixing pig iron into large foundry containers holding pools and puddles of molten-hot iron ore, stirred with a prod so that the carbon could be released by air contact, produced wrought iron (the quality of which was that of wrought iron laboriously forged through the bloomery process, found elsewhere in the world, like Europe and the Near East). This iron-puddle-and-prod process was called "Chao," or "stir-frying" in English. The Chinese soon figured out that they could smelt both wrought iron (low carbon content) and brittle cast iron (high carbon content) together, upon which they discovered that they could form a formidable new, durable, less-brittle iron-carbon alloy of the desired mediocre carbon level (roughly 2% carbon), in other words, steel.

I've always thought that with Chinese armor, fish-scale and lamellar armors using small woven, linked, or rivited plates of armor were used for protection, and the only large single pieces of armor that could be compared to the heavy mounted cavalry knights of Medieval and Renaissance Europe would be fully-cast, single-piece iron/steel helmets and breast-plates. However, this Tang-era (618 - 907 AD) statue posted below, found amongst many others in the Caves of Mogao at Dunhuang, China, suggest that the Chinese also had large plates of armor to protect the shins of their legs and wrists of their arms as well. Notice the guy on the right and what he is wearing...

Food for thought,

Eric Edited by Preobrazhenskoe - 18-Aug-2006 at 16:40 |

|

|

|

Omnipotence

Baron

Joined: 16-Nov-2004 Online Status: Offline Posts: 494 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 18-Aug-2006 at 23:34 Posted: 18-Aug-2006 at 23:34 |

|

^That statue is Tang-styled alright, though there are arguments about whether the breastplate is a true "plate".

Edited by Omnipotence - 18-Aug-2006 at 23:34 |

|

|

|

Preobrazhenskoe

Consul

Joined: 27-Jul-2006 Location: United States Online Status: Offline Posts: 398 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 25-Aug-2006 at 11:34 Posted: 25-Aug-2006 at 11:34 |

|

What? What speculation is there to suggest that a breastplate is not a true plate? I'd like to see this. And for that matter, the statue clearly depicts large plates of armor shielding his arms and legs as well, something that I haven't seen to often in Chinese armor, which consists of the fish-scale and lamellar types of sewn, riveted, or chain-linked small plates of armor in pattern.

Eric

|

|

|

|

chizwiz

Immortal Guard

Joined: 18-Jul-2010 Location: SC Online Status: Offline Posts: 1 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 18-Jul-2010 at 18:57 Posted: 18-Jul-2010 at 18:57 |

|

What is the date of the Ming Dynasty painting showing the 3-barrel hand cannon? What is the earliest date for that particular gun? I have one and know little about it. Thanks, Jim |

|

|

JC

|

|

|

|

RollingWave

Janissary

Joined: 29-Jul-2005 Online Status: Offline Posts: 15 |

Quote Quote  Reply Reply

Posted: 19-Jul-2010 at 01:36 Posted: 19-Jul-2010 at 01:36 |

|

I'm not sure about earliest known date, though the coommon theory seem to be the reign of Jiajing emperor, which is early to mid 16th century, I do know for a fact that they were used heavily during the late 16th early 17th century, aka the last stage of the empire.

While the Ming had various home made or import / copy deisgn arquebus at the time, they favored this weapon more, the reasonings tend to be that

A. it can double as a melee weapon, thus making it less of a liability than arquebus in that situation

B. it doesn't need to be held near the face, making it safer in the event of a implosion (always a hazard for early fire arms, and the Ming's craftsmanship quality on mass produced products wasn't exactly good).

C. in short burst, it packs a bigger punch. (it's more difficult to reload than a arquebus , but it can fire many more shots in one burst. and it's not like arquebus are fast reloading weapons either.)

D. the gunpowder mechanism is simplier, and more importantly less suspect to heavy wind. which is always a problem in the open northern frontier of the Ming, a later Qing manuel noted that arquebus aren't suitable for the north because "when you open the hatch the strong wind often blows away the gunpowder before final ignition."

|

|

|

|

Post Reply

|

| Forum Jump | Forum Permissions  You cannot post new topics in this forum You cannot reply to topics in this forum You cannot delete your posts in this forum You cannot edit your posts in this forum You cannot create polls in this forum You cannot vote in polls in this forum |

Bulletin Board Software by Web Wiz Forums® version 9.56a [Free Express Edition]

Copyright ©2001-2009 Web Wiz

This page was generated in 0.141 seconds.

Copyright ©2001-2009 Web Wiz

This page was generated in 0.141 seconds.

Printable Version

Printable Version Google

Google Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Windows Live

Windows Live Yahoo Bookmarks

Yahoo Bookmarks reddit

reddit Facebook

Facebook MySpace

MySpace Newsvine

Newsvine Furl

Furl Topic Options

Topic Options