Regardless of whether you are seeking the best debate topics for students or need something about History or Art, choosing issues for academic papers can be challenging.

Art is a very complex topic to write about if you’re not good at it. You don’t get the symbols, and you don’t understand the artist’s ideas at all. We suggest you to write research papers and essays about art history instead. It’s more about knowledge and research, especially if the request is to write my essay for me, than about understanding the thoughts and feelings of a person you’ve never met in your life.

Check out 60 art history research paper topics and ideas for brilliant essays, prepared by our essay writer service. Plus, we have great art history research paper samples that will serve as a good template for your writing.

Table of contents

- Art history research paper topics: Women in Art

- Art history research paper topics on ancient civilizations

- Art history research paper topics: the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

- Art history research paper topics: 18th century

- Art history research paper topics: 19th century

- Art history research paper topics: 20th century

- Art history essay topics: argumentative and analytical

- Art History Research Paper Topics

- Conclusion

You can use our ideas as a basis for your own topic or grab any of them and discuss them in your paper. In any case, as a history essay writer, you can rest assured that you will come up with a question that is relevant and focused enough for your academic research.

Art history research paper topics: Women in Art

The question of women’s place in different spheres has always been a decidedly tricky one. In many fields, women had to apply a great deal of effort to become renowned, no matter how good their research was, striving for genuine recognition rather than simply having their research papers for sale. Thus, the issue of ladies in fields like art is still on point, and it is interesting to see the development of women experts in the industry. Here is a list of fresh and relevant art essay topics that present the figure of women in this field.

- The Influence of Women Artists in the Surrealist Movement

- Reclaiming the Muse: The Role of Women as Subjects in Art History

- The Evolution of Feminist Art: From Guerrilla Girls to Contemporary Voices

- The Hidden Legacy of Women Artists in the Italian Renaissance

- Female Patrons and Collectors: Women’s Influence on Art History

- Portraiture and Power: The Representation of Women in Baroque Art

- Breaking Boundaries: Women Abstract Artists in the 20th Century

- Art and Motherhood: The Dual Role of Female Artists in the 20th Century

- The Rise of the Female Artist in the Post-War Art World

- Gender and Identity in Contemporary Art by Women of Color

Art history research paper topics on ancient civilizations

This subject is for those who want to dig deep! The ancient world is full of mysteries and secrets. Do you like Indiana Jones and Lara Croft movies? These topics will allow you to feel the spirit of history!

- Features of sculptures in Ancient Greece. The influence of science on sculptures.

- Compare and contrast Mesoamerican and Egyptian pyramids.

- The origin of the traditional Japanese and Chinese costumes and their impacts on culture.

- What were the main reasons for the Roman artistic style shift in the 4th century?

- The most famous pieces of Mesopotamian art.

- Compare and contrast the Egyptian and Greek canons of proportions.

- Hinduism in early Indian art.

- Construction of the Great Wall of China.

- The origins of Greek theater.

- The Scythian gold adornments.

Wanna learn more about the function of Egyptian Art? Check out this sample!

Art history research paper topics: the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Day and night, life and death, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance – the contrast between these two epochs amazes everyone who is eager to learn more about them. Don’t hesitate to join their ranks!

- Biblical motives in Leonardo da Vinci’s early paintings.

- The role of Mughal paintings in forming the image of the Mughal kings in India.

- Ancient Greek motifs in Michelangelo’s sculpture, “David.”

- Why was Renaissance art so overwhelmed with Christian symbols and themes?

- The peculiarities of Raphael’s paintings.

- The representation of humanistic ideas in Renaissance art.

- What determined the main principles of Medieval art?

- The elements of Gothic architecture.

- The role of troubadours and trouvères in the development of European culture.

- Renaissance women’s clothing and beauty standards.

The Middle Ages are associated with mostly religious themes. Check out our Jesus Christ research paper about Medieval pictures.

Art history research paper topics: 18th century

The 18th century was a time of glorious musicians and elegant architecture. Learn more about the Baroque style, Neoclassicism, and the Viennese School with our topics.

- The main features of late Baroque architecture.

- The history of creating “The Death of Sardanapalus” and its place in Eugène Delacroix’s paintings.

- What was the influence of the Industrial Revolution on art development?

- The combination of old traditions and new ideas in Neoclassicism sculpture.

- Compare and contrast the Baroque and Rococo art styles.

- The literature of the Enlightenment: the main authors.

- Famous composers of the First Viennese School.

- Rococo interior design.

- Erotic novels by the Marquis de Sade.

- The importance of Denis Diderot’s critiques for 18th-century French art.

The 18th century wouldn’t be the same without the French Revolution. Our expert compares french Revolution paintings and Greek art in this research paper sample.

Art history research paper topics: 19th century

Artists are very sensitive people. They often sense the changes to come and express these feelings in their paintings. The artists of the 19th century are no exception. See for yourself with the help of our list.

- Edgar Degas and his “dancing” paintings.

- Key changes in methodology in paintings in the epoch of Impressionism.

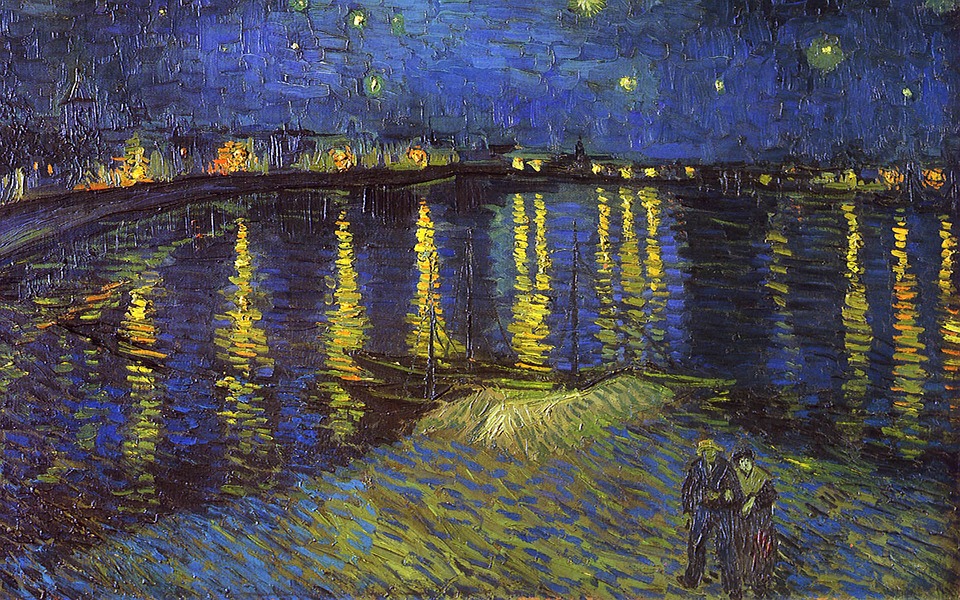

- Coloristics of “The Starry Night” by Vincent van Gogh.

- What is so special about the carving “The Veiled Virgin” by Giovanni Strazza?

- What is so special about the light in Monet’s “Sunrise”?

- How were Victorian beauty standards depicted in art?

- The connection between French caricatures of the 19th century and Goya’s prints.

- Why do paintings by Francisco de Goya have an important historical role?

- The peculiarities of Paul Gauguin savage art.

- Why did the critics reject Édouard Manet’s paintings at first?

Read about the beautiful art of Impressionists in our Impressionism research paper sample.

Art history research paper topics: 20th century

In the 20th century, the world went crazy: wars, revolutions, demonstrations, space exploration, etc. Changes touched each sphere of human life. Artists couldn’t stand aside and launched the beginning of new art movements: Surrealism, Cubism, Futurism, and others.

- Main similarities and differences between the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles.

- Surrealism in Salvador Dali’s sculptures.

- Different mannerisms in Pablo Picasso’s paintings, from Art Nouveau to Cubism: evolution, or just separate periods in his oeuvre?

- The combination of different art styles in the painting “The Kiss” by Gustav Klimt.

- The psychology of color in Kazimir Malevich’s works.

- Realistic and artificial motifs in Jasper John’s “Flag.”

- What are the peculiar features of Art Deco hotels in French Indochina?

- The most frequently used symbols in Frida Kahlo’s paintings.

- The unique technique in Jackson Pollock’s art.

- The basic principles of Futurism.

Salvador Dali was a truly extraordinary person. Learn more about his relationship with Gala in our essay about art history!

Art history essay topics: argumentative and analytical

Surprisingly, analytical thinking and argumentative strategies can be applied to art. The following topics will be perfect for your essay about art history:

- Was Hitler’s artwork actually good?

- Is the majority of modern art a scam?

- What were the primary aims of the camera obscura and how did it change throughout the years?

- Compare the critiquing styles of Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg.

- What is so unusual and unique in Russian icons?

- The evolution of the uncovered body in paintings of various periods.

- Why is “Guernica” by Pablo Picasso the most influential painting of the 20th century?

- Can the Middle Ages be considered as a period of decline in art?

- Why did Victor Hugo suggest that printing would kill architecture in his novel “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”?

- Is primitivism real art?

Futurism is a perfect topic to argue about, as it is very ambiguous. Have a try with our Futurism research paper.

Art History Research Paper Topics

Art history is a vast and dynamic field that not only documents aesthetic movements but also reflects cultural, political, and social change across time. From the religious symbolism of the Renaissance to the rebellious messages of modern street art, the study of visual art offers valuable insight into human experience. The following research topics span a broad range of historical periods and artistic approaches, providing rich ground for academic exploration.

To help guide your research, we’ve compiled a list of diverse and thought-provoking art history essay topics ranging from the Renaissance to modern digital art. These topics are structured with overviews, key artworks, and suggested analytical angles, making them ideal for essays or more in-depth research projects.

1. The Role of Women in Renaissance Art

Overview: Explore how women were portrayed in Renaissance art and how female artists contributed to the movement.

Focus Points: Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, Artemisia Gentileschi’s works.

Angle: Compare the objectification of women vs. agency of female artists.

2. Symbolism and Allegory in Northern Renaissance Art

Overview: Analyze how complex religious and moral symbolism was embedded in works from the Northern Renaissance.

Focus Points: Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Angle: Interpretation of everyday objects and their spiritual meanings.

3. Art as Political Propaganda in the Baroque Period

Overview: How monarchies and the Church used Baroque art to assert power.

Focus Points: Louis XIV and Versailles, Bernini’s works for the Vatican.

Angle: Theatricality and control in visual imagery.

4. Romanticism vs. Neoclassicism: A Cultural Rebellion

Overview: Contrast the restrained ideals of Neoclassicism with the emotional expression of Romanticism.

Focus Points: Jacques-Louis David vs. Francisco Goya or Delacroix.

Angle: How historical context (e.g., French Revolution) influenced style and ideology.

5. The Influence of Japanese Art on European Impressionism

Overview: Study the impact of Japonisme on 19th-century European painters.

Focus Points: Monet, Degas, and Van Gogh’s incorporation of ukiyo-e styles.

Angle: Cross-cultural exchange in technique and perspective.

6. Cubism and the Deconstruction of Form

Overview: Discuss how Cubism revolutionized artistic representation.

Focus Points: Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Braque’s still lifes.

Angle: Rejecting linear perspective and embracing abstraction.

7. Feminist Art of the 20th Century

Overview: Explore how feminist movements influenced art and challenged traditional narratives.

Focus Points: Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, Guerrilla Girls.

Angle: Art as protest, representation, and reclamation.

8. The Harlem Renaissance: Art as Identity

Overview: Explore how African American artists used visual art to reclaim identity and resist oppression.

Focus Points: Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley.

Angle: Merging modernism with African heritage.

9. Art and Trauma: Post-War Expressionism

Overview: Analyze how the trauma of war shaped Expressionist and Dadaist movements.

Focus Points: Otto Dix, George Grosz, Hannah Höch.

Angle: Psychological response to violence and chaos.

10. Street Art and the Legitimization of Graffiti

Overview: From vandalism to high art: the evolution of street art in public and gallery spaces.

Focus Points: Banksy, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring.

Angle: Who decides what is “art”?

11. The Representation of Religion in Byzantine Art

Overview: Examine how spiritual themes shaped visual culture in the Byzantine Empire.

Focus Points: Mosaics in Hagia Sophia, icon paintings, Christ Pantocrator.

Angle: Sacred art as a form of theological instruction and imperial authority.

12. The Evolution of Portraiture from the Renaissance to Modernity

Overview: Trace how the depiction of individuals evolved in style, meaning, and technique.

Focus Points: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Van Gogh’s self-portraits, Chuck Close.

Angle: Changing ideas of identity and self-representation across time.

13. Mythology in Classical and Renaissance Art

Overview: Explore how myths were visualized and reinterpreted through centuries.

Focus Points: Raphael’s Galatea, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Greek vase painting.

Angle: Myth as cultural narrative and symbolic storytelling.

14. Islamic Art and the Geometry of the Divine

Overview: Investigate the symbolic power of pattern, symmetry, and calligraphy in Islamic art.

Focus Points: Alhambra Palace, Qur’anic manuscripts, Persian miniatures.

Angle: Non-figurative forms as expressions of spirituality and transcendence.

15. The Bauhaus Movement and the Unity of Art and Design

Overview: Study how Bauhaus revolutionized the relationship between form and function.

Focus Points: Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, architecture and typography.

Angle: The fusion of fine art, industrial design, and architecture.

16. The Surrealist Exploration of the Unconscious Mind

Overview: Examine how surrealist artists visualized dreams, trauma, and desire.

Focus Points: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst.

Angle: Freudian psychology and its impact on visual surrealism.

17. Colonialism and the Appropriation of Indigenous Art

Overview: Analyze how colonial powers represented or exploited indigenous aesthetics.

Focus Points: Museum collections, tribal art in modernist works, primitivism.

Angle: Who owns culture? Ethical debates in curation and repatriation.

18. The Rise of Photography as an Art Form

Overview: Track the evolution of photography from documentation to fine art.

Focus Points: Alfred Stieglitz, Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin.

Angle: Photography’s challenge to painting and its role in social critique.

19. Environmental Art and the Land Art Movement

Overview: Explore how artists used nature as canvas and medium.

Focus Points: Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, Andy Goldsworthy, Agnes Denes.

Angle: Art as ecological message and impermanence.

20. Digital Art and the Transformation of Creativity in the 21st Century

Overview: Investigate how digital tools are redefining what it means to make and experience art.

Focus Points: AI-generated art, NFTs, virtual installations.

Angle: Innovation, authorship, and the future of artistic value.

Conclusion

These topics highlight the interdisciplinary nature of art history, where visual culture intersects with politics, identity, gender, and global influence. Whether focusing on Renaissance symbolism or modern feminist statements, each theme offers a unique lens through which to understand how art both reflects and shapes the world. Choose a topic that resonates with your interests, and let the artwork guide your critical analysis and historical interpretation.

We’ve collected these 60 exclusive ideas for your research papers and essays about art history. You can find even more topics (100+!) right here. Your task is to choose the most attractive one for you, and start writing.

Moreover, students know that if they have no idea how to write a diagnostic essay or what is an appendix in writing, they can always get answers on our blog. Our professional writers work hard to not only provide custom assistance with any college paper but also to create hundreds of writing guides to help college learners master their writing skills and succeed in their academic careers.

We know that art can be complex and hard to understand. If the writing process seems too challenging for you, we’re always ready to provide you with support. Our experts write well-structured and informative texts on any topic. If you don’t know how to write a coursework, contact us anytime to get help.

Contact us any time to get helpful art history research paper samples easily!