Was the extermination of buffalo a genocide?

Printed From: History Community ~ All Empires

Category: Regional History or Period History

Forum Name: History of the Americas

Forum Discription: The Americas: History from pre-Colombian times to the present

URL: http://www.allempires.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=22360

Printed Date: 20-May-2024 at 00:45

Software Version: Web Wiz Forums 9.56a - http://www.webwizforums.com

Topic: Was the extermination of buffalo a genocide?

Posted By: Guests

Subject: Was the extermination of buffalo a genocide?

Date Posted: 01-Nov-2007 at 12:50

|

One of the major killings of an species was the killing of the buffalo in the times the railroads connected the U.S. from coast to coast. For fun, people started to kill them all over the great plains of the U.S. driving them to near extinction. The main victims, besides the animals, were the Amerindians that lived hunting that animal.

What was the intention behind the nearly extermination of the Buffalo by the European settlers of the U.S.? Do they wanted to exterminate the Natives of the praries by hunger? How many native americans died of hunger when the buffalo started to dissapear?

What was the impact in theirs psycology and pride? Will it ever recover the buffalo to the numbers of ancient times?

More about it:

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntecoindian/essays/buffalo.htm - http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntecoindian/essays/buffalo.htm

Buffalo Tales: The Near-Extermination of the

American Bison

Shepard Krech III, Brown University

©National Humanities Center |

|

|

Bison, Yellowstone National Park

|

NPS | |

|

| Prior to the arrival of Europeans and their powerful, transforming products, desires, and structures, American Indians possessed extensive knowledge about the environments in which they lived and made sense of living beings in myriad culturally appropriate ways. They drew on an extraordinary variety of animals and plants in daily subsistence; yet specific animals or plants, because of their prominence, came to stand for entire regions and groups of people: seals for Inuit, caribou for northern Indians, acorns and deer for native Californians, salmon for Northwest Coasters, corn for the Southwest Puebloans, Hopi and Zuni. None was more prominent than the buffalo.

The buffalo was first and foremost of utmost significance to people of the plains and prairies. In a very different way, its crucial standing was underscored by native people generally, after the spread of Plains traits and imagery—especially the eagle-feathered bonneted warrior-hunter astride his horse in pursuit of meat and honor—ultimately to symbolize the North American Indian. Moreover, no story of wildlife decline in North America is more widely known than the demise of the buffalo. It is one of the most important stories in the environmental history of North America.

|

ca. 1873

|

National Archives

|

"no story of wildlife decline in North America is more widely

known than the demise of the buffalo"

| |

Buffaloes once ranged much of the continent, from the east to west coasts, and from Canada's Northwest Territories in the north and Mexico in the south. The center of population was the great western grasslands, and the press of new arrivals from Europe soon resulted in their extermination in the peripheries of their territory; east of the Mississippi they were extinct by 1833.

|

|

| What strikes the stranger with most amazement is their immense numbers. I know a million is a great many, but I am confident we saw that number yesterday. Certainly, all we saw could not have stood on ten square miles of ground. Often, the country for miles on either hand seemed quite black with them. |

An Overland Journey, from New York to

San Francisco in the Summer of 1859

Horace Greeley, 1860

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalokwgreeley.htm,%20greeley,%20width=500,height=300,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - full text

|

| Suddenly a cloud of dust rose over its crest, and I heard a rushing noise as of a mighty whirlwind, or the charging tramp of ten thousand horse. I had not time to divine its cause, when a herd of buffalo arose over the summit, and a dense mass, thousand upon thousand, gallopped, with headlong speed, directly upon the spot where I stood. . . . Still onward they came—Heaven protect me! it was a fearful sight. |

"Scenes in the West; or,

A Night on the Santa Fe Trail, No. III,"

Philip St. George Cooke, Southern Literary Messenger, February 1842

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalokwscenes.htm,%20scenes,%20width=550,height=300,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - full text

| |

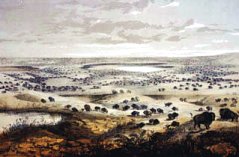

| From 1600 to 1870, the number of buffaloes was almost always uncertain: observers used language like immense numbers, countless numbers, countless thousands, dense masses, one great mass, herds that blackened the plains, bulls roaring like distant thunder or like a river's rapids, bison in such numbers that they drink a river dry or the ground trembles with vibration when they move. The images were striking. The annual migration across the prairies awed all who experienced it. Because there were so many buffaloes, natural disasters were magnified: thousands, if not tens of thousands, froze to death in blizzards, drowned crossing rotten ice, or mired in muddy bogs.

Estimates of numbers range widely. Some thought (clearly in error) that there were hundreds of millions of even billions; others estimated (far more reasonably) numbers at from 30 to 1000 million in A.D. 1500. Ernest Thompson Seton, the naturalist, was the first to estimate population on the basis of what was called "range allowance" (or carrying capacity) and settled on at least 60 million. Since his day the tendency has been to lower the estimates because bison were unevenly distributed over their range and because drought periodically struck the Plains. According to Dan Flores, an historian, no more than 30 million bison roamed the Plains prior to the arrival of the horse.

|

| Iowa, 1906 |

Library of Congress

| |

|

Arapaho camp

with buffalo meat drying

Kansas, 1870

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalomeatlg.htm,%20buffalomeat,%20width=590,height=400,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

|

National Archives |

"For thousands of Plains Indians . . .

the buffalo was unquestionably paramount."

| |

|

| For thousands of Plains Indians—people like the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Assiniboin, Crow, Cheyenne, Shoshoni, Arapaho, various Sioux or Dakota people, Comanche, and others—the buffalo was unquestionably paramount. For many it was "real" food, and they consumed an incredible variety of bison parts: meat, fat, organs, testicles, nose gristle, nipples, blood, milk, marrow, fetus. They had broadly defined canons of edibility but preferred cows over bulls and greatly desired humps, tongues, and fetuses.

But the buffalo represented more than food. For many it provided over one hundred specific items of material culture. Day or night, Plains Indians could not ever have been out of sight, touch, or smell of some buffalo product. It was the era's Wal-Mart.

(part 2 of 4)

|

Gilcrease  |

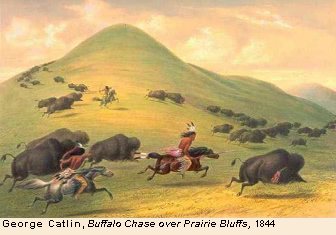

George Catlin, Catlin and His Indian Guide Approaching Buffalo under White Wolf Skins, 1846-1848

| |

|

| To obtain an animal so critical to their well-being, Plains Indians developed a number of solitary and communal hunting techniques. Sometimes a man clothed in a buffalo robe or wolf skin might stalk the animal carefully. Beneath the skin of a wolf he might pique the curiosity of buffaloes that would meander within range of his arrows. Buffaloes have sharp smell and hearing but are both curious and, the bulls at least, relatively fearless, so this type of hunting was not as difficult as it might seem. At other times many hunters drove bison onto soft ice or into deep snow, a ravine, a box canyon, or enclosure or pound. In these places the animals could readily be killed.

The most efficient technique was what Crow Indians called "driving buffalo over embankments," which involved enticing and leading buffaloes to the edges of cliffs or bluffs up to seventy feet high, then driving them over to instant death or a broken back or leg or other crippling incapacity, ended by a thrust from a lance or blow from a stone maul. This hunt involved an entire society: the "chaser" or "runner," who possessed special skills and knowledge, led animals he had found toward the precipice, where other people, hidden behind trees or rock piles, waved blankets and shouted the animals onward to their doom at the base of the cliff. Yet others waited to kill, butcher, and transform buffaloes into useful products. These communal techniques were tightly controlled by leaders and societies whose duties were to police the hunt, preventing any single man from premature action that might spoil the attempt to obtain such an important resource for all.

Ritual was often important for the success of such a hunt. To call the buffalo near, some Indians danced and others used sacred buffalo stones kept in beaver bundles, esoteric knowledge, songs, or sweetgrass. Smoking tobacco and offering the pipe to propitiate whoever had power to ensure success were common. Certain men possessed special power or knowledge as, for example, the "chaser" or "runner" called "He-Who-Brings-Them-In" by the Assiniboins, who trolled buffaloes into a narrowing V-shaped lane and would yell and startle the animals into a panicked run toward the trap or cliff edge.

For some Indians, the center of a circular enclosure into which buffalo would be driven was ritual space for the erection of a sacrificial pole or display of painted, feather-bedecked buffalo skulls, and for addressing buffaloes with respect prior to the killing. Failure in the hunt, if not due to an impetuous hunter spoiling it for others, was easily ascribed to improperly performed ritual.

The average mature bison weighed some 700-800 pounds and yielded 225-400 pounds of meat, and communal hunts resulting in the deaths of dozens or hundreds of animals (30, 60, 100, and even 600, 800, and 1000 were reported killed) produced fantastic quantities of meat: 50 cows, for example, yielded 11,000-20,000 pounds of usable meat. Many European observers were struck by gourmandizing as well as by what struck them as subsequent "profligacy" or "indolence." At times, Indians used everything. But on occasions they did not, and the observers remarked upon "putrified carcasses," animals left untouched, or Indians who took only "the best parts of the meat." Sometimes Indians were said to kill "whole herds" only for the fat-filled tongues.

|

|

|

National Gallery of Art  |

George Catlin

After the Buffalo Chase - Sioux, 1861/1869

|

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffaloafterchaselg.htm,%20buffalochase,%20width=570,height=400,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

|

"Why did Indians sometimes behave in ways

antithetical to today's conservation?"

| |

| Why did Indians sometimes behave in ways antithetical to today's conservation (which at heart means to prevent waste and to manage a resource to prevent depletion)? Among possible reasons are

- the likelihood that in any given year there were tens (or hundreds) of thousands of buffaloes within sight

- the need to ensure an adequate supply of an animal on which they were thoroughly dependent

- the difficulty of halting midway a drive over a jump

- the enormous quantities and weights that awaited butchering and processing after some hunts

- the preference for cows for their palatable meat and more easily worked hides

- the preference for delicacies like the hump, tongue, marrow, and fetus.

|

|

National Gallery of Art  |

George Catlin

Buffalo Dance - Mandan, 1861

|

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalomandanlg.htm,%20buffalomandan,%20width=590,height=470,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

|

"religion permeated the hunt"

| |

|

| Other reasons may have come from certain beliefs, which, to Indians who held them, were perfectly rational. Plains Indians animated buffaloes (and other animals) as other-than-human persons. In a former day, Plains Indians collectively believed, men and women conversed with, fought, killed, had sexual intercourse with, shared food with, and were kin to animals including buffaloes. Human-animal relationships ranged from beneficial to harmful, and were regulated by expectations and obligations similar to those that governed relations between human kin and allies. For Plains Indians, the buffalo was either the most sacred animal or one of the most important beings in which power was distributed. Thus religion permeated the hunt, from ritual intended to "call buffaloes" within range, to prayers offered to the animals before they were killed; and Indians, concerned above all to ensure a successful hunt, addressed buffaloes as sentient beings, animating them in ways that made perfect sense to them even if not to alien observers of European descent.

This might help make sense of certain conservation- and ecology-related beliefs and action. For example, native people sometimes tracked down buffaloes that wandered away from the base of a jump or from an enclosure into which a herd had been driven, regardless of how many had died. It might seem contradictory to kill more than is needed, but not given the belief that buffaloes that escaped would warn others away and spoil future hunts. What at first glance seems odd is in its cultural context rational.

Another belief bears on ecological thought, which at base is systemic and concerned with interrelationships among organisms and their environment. Some Indians thought that when buffaloes disappeared for the season, they went to lake-bottom grasslands, and that when they reappeared they came from those habitats. Some had seen buffaloes emerging from certain caves or knew of others who had witnessed this. Such a belief would have fundamental consequences for how an ecological "system" is conceptualized. Plains Indian ecological spaces would not all be within the parameters of a western ecologist's ecosystem. It is easy to see how a belief of this nature would get in the way of conservation of a declining resource under conditions like those obtaining on the nineteenth-century plains. If buffaloes did not return when they were expected or in the numbers anticipated, it was not because too many were being killed but because they had not yet left their lake-bottom prairies. How could one kill too many if one held to this belief? How could buffaloes possibly go extinct?

|

George Catlin

Prairie Meadows Burning

1861/1869

|

National Gallery of Art | |

|

|

The decline of the buffalo is largely a nineteenth-century story. The size of the herds was affected by predation (by humans and wolves), disease, fires, climate, competition from horses, the market, and other factors. Fires often swept the grasslands, sometimes maiming and killing buffaloes. Millions of horses in Indian herds competed for grasses. Drought was perhaps most significant; severe prior to the fifteenth century, and episodic in the eighteenth, it might have been worst at the very moment when other pressures converged in the early years of the decades from 1840 to 1880.

Yet no matter the impact from drought, horses, or fires, what doomed the buffalo most were (1) the commodities markets for buffalo tongues, skins, meat, and robes; and (2) the railroads, which provided the means of transportation to rapidly expanding European-American populations.

|

|

"Wanton Destruction of Buffalo"

in W. E. Webb, Buffalo Land, 1872

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalowantonlg.htm,%20buffalowanton,%20width=800,height=500,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

| |

|

|

|

1872

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalodeadsnowlg.htm,%20buffalodeadsnow,%20width=600,height=480,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

|

National Archives

|

"the fury of the slaughter for hides and other products"

| |

|

| Again largely a nineteenth-century tale, the final stage from 1867 to 1884 was notable for the fury of the slaughter for hides and other products. In 1867 the first of five railroads split the herd in the heart of buffalo range, a process repeated again and again. Provisioners like Buffalo Bill Cody, sportsmen, farmers, and ranchers who craved the prairies for crops and cattle—all placed new pressure on bison. The railroads made transportation of buffalo hides easy and cheap, so market hunters flooded in, wasting three to five times the numbers they killed. The carnage from herds already depleted by other factors defied description: 4-5 million killed in three years alone. The commercial hunt was finished by the fall of 1883.

|

|

National Archives  |

Hide yard with 40,000 buffalo hides

Dodge City, Kansas, 1878

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalohideyardlg.htm,%20buffalohideyard,%20width=570,height=380,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - enlarge image

| |

| Indians, confined to reservations and distressed from hunger, took part until the bitter end—the Piegan until "the tail of the last buffalo" disappeared. The final shipment of hides took place in 1884. With very few exceptions, the buffalo was gone and bone collectors scooped up all the remains they could find for shipment east where they were processed into phosphate fertilizer.

|

1870

|

National Archives | |

Thirty years ago millions of the great unwieldy animals existed on this continent. Innumerable droves roamed, comparatively undisturbed and unmolested, . . . Many thousands have been ruthlessly and shamefully slain every season for past twenty years or more by white hunters and tourists merely for their robes, and in sheer wanton sport, and their huge carcasses left to fester and rot, and their bleached skeletons to strew the deserts and lonely plains.

"In the Prime of the Buffalo," J. F. Baltimore

The Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine

November 1889

javascript:%20newWindow%20=%20openWin%28%20buffalokwprime.htm,%20prime,%20width=540,height=300,toolbar=1,location=0,directories=0,status=0,menuBar=0,scrollBars=1,resizable=1%20%29;%20newWindow.focus%28%29 - full text

| |

Today, one hundred years later, the buffalo has returned from the brink of extinction to roam the grasslands again in Yellowstone and beyond. Feared by farmers for diseases like brucellosis that they might carry to cattle herds, their fate beyond Yellowstone is uncertain, although Indian people have joined forces in a cooperative effort to save animals wandering from Yellowstone from the rifle, and to raise viable herds of this formerly vital, and currently deeply symbolic, animal. Yet it is no coincidence that in today's changing economy, when many Indians talk of the return of the buffalo, they mean not the animal but casinos.

|

Carsi/CAS

| |

GUIDING STUDENT DISCUSSION / SCHOLARS DEBATE

|

SHS of North Dakota  |

Stanley, Herd of Bison near Lake Jessie

[North Dakota], 1853-1855

|

|

|

Bison herd

Yellowstone National Park

ca. 1990

|

NPS

| |

|

| As a central element in the history and imagery of the West, the buffalo, and especially its demise, has been the focus of arguments for well over one hundred years. To set the stage for discussion, it helps to try to imagine the landscape at the outset of the nineteenth century—the landscape and flora and fauna seen by those who explored and traveled the West and recorded their impressions. The best place to begin is with Lewis and Clark's words; an accessible edition is Frank Bergon's Journals of Lewis and Clark (1989), which focuses on natural history, and there are numerous excerpts on the Web (see online resources). A useful (although very different) exercise would be to contemplate through careful description the changes in that landscape today. Lewis and Clark's trip is coming up for bicentennial commemoration (2003-2006), which should provide fresh material from a range of popular sources to engage student interest.

|

Denver PL  |

Ute children

on a buffalo hide

Utah, ca. 1873

|

| |

|

| The second task is to engage students in discussion about the meaning of buffalo for Plains Indians. John Ewers's The Blackfeet (1958), Joseph Medicine Crow's From the Heart of Crow Country (1992), and the more general works by Francis Haines ( The Buffalo, 1970/1995), Tom McHugh ( The Time of the Buffalo, 1972) and David Dary ( The Buffalo Book, 1974/1989) are all useful sources. What buffalo meant, of course, will depend on whether the discussion focuses on subsistence, clothing, and other

items of material culture, or on myth, religion, or some other context in which buffaloes in some form appeared. Students can learn a great deal simply by taking up (in the imagination) the sensory world created by buffalo products that made existence and lifestyles possible on the Plains for generations, and by reflecting on the differences not only between what they wear, eat, or use but about the systems of production that resulted in these products.

The great story about the buffalo is the story of their demise in the nineteenth century. The literature is voluminous, the arguments acrid and complex. In the last century some argued that Indians played a role in the near-extinction of the buffalo, others that nonIndians deliberately sought to kill the animals in order to exterminate the Indians themselves. It might help to sort the arguments into several categories:

- Indian hunting itself and Indian need for buffaloes to sustain daily life. Both Dan Flores ("Bison Ecology and Bison Diplomacy," Journal of American History, 1991) and I (The Ecological Indian, 1999) discuss the data.

- Whether Indians were conservationists when it came to buffalo. This is a complex issue and one that I have written about at length elsewhere (The Ecological Indian). To answer the question requires a working definition of conservation and an appreciation for American Indian thought about animals and their environments, that is, an appreciation for ethnoecology—the ecological thought of a people (ethnic group). I suggest close reading of the Introduction and the chapter "Buffalo" in The Ecological Indian. It will be important to focus on animals in general as animate beings, and on comprehending the spaces in indigenous ecosystems. This would be a valuable way to give students an appreciation for ways of thinking about nature that, though radically different from western science, are nonetheless rational to the thinkers.

- The demise of the buffalo.

Here the best place to begin is with Dan Flores's seminal essay "Bison Ecology and Bison Diplomacy," but if this is difficult to obtain, then Drew Isenberg's The Destruction of the Buffalo (2000) is an excellent recent source. The story is told in the general works by Dary and McHugh referred to earlier. The larger environmental context for the decline of the buffalo was set by climate, drought, disease, fire, horses, cattle, barbed wire, ranchers, railroads, market hunters, and so on. It was driven for the most part by the commodification of the buffalo—tongues, hides, and other parts as highly desired commodities in a greatly expanding marketplace. The demise requires systematic explanation. It resists easy sound bites despite the oft-stated desire of students for straightforward black-and-white answers to complex problems. And it might help to explore whether or not there is an Indian explanation and a nonIndian explanation of the buffalo's demise, or is this too simplistic? At the end of the day, what evidence satisfies your students in this or any other historical explanation?

|

|

Bison cow and calf

|

Corsi/CAS | |

| To bring the buffalo's story up to date, begin with the Epilogue of The Ecological Indian and proceed to the web resources that accompany this essay. Several involve the Indian effort to provide safe haven for animals that leave the confines of Yellowstone National Park. Finally, whether the story of the buffalo will be repeated in the new century, with other species, can be explored to extend your discussion into current environmental, economic, and land use issues.

|

Replies:

Posted By: Adalwolf

Date Posted: 01-Nov-2007 at 14:41

It was genocide to the Indians and to the buffalo.

-------------

Concrete is heavy; iron is hard--but the grass will prevail.

Edward Abbey

|

Posted By: ehecatzin

Date Posted: 04-Nov-2007 at 02:03

|

It was a genocide to the indiand and the buffalo, but it was also a way to kill the native culture, as the buffalo played a central role in it, like the idea that if you kill the buffalo you kill the indian spirit.

|

Posted By: Guests

Date Posted: 04-Nov-2007 at 12:21

|

They also killed the economical support for the independence of the Indians.

By the way, once I eat buffalo meat in a Canadian restaurat. Some farmers are growing domesticated buffalos in that country, in the same way we grow ostriches in Chile. Well, the food was the most tasty I ever tried with a superb texture. I had a deep feeling of lost.

|

Posted By: Panther

Date Posted: 05-Nov-2007 at 00:20

|

Not to be unfairly critical pinguin, but your poll could have used a little more brushening up? As it currently stands, i would have to go with the end result of the policy, which is too make them sadly dependent on the good or bad will of the state. A very good case of not allowing this country's government too keep growing into the ultimate nanny state, if i ever saw one?!

Was it genocide? Only against the North American bison. Genocide against the Indians? No, i think that pretty much misses the point of the ultimate aim of the US government in bringing the centuries long war with the indigenous population too an end! Did it destroy their culture and way of life? For some it unarguably did. But for many other tribes, it only weakened them to a certain extent of acquiescence, but did not in the end, destroy them or their belief's!

Case in point, i know quite a few guys who are life-long, card carrying members of any one particular tribe (But, predominantly cherokee or comanche), but in this point of reference, i am talking about Oklahoma... who still attend their ancestors tribal ritual gatherings. That is... they are the ones who chose not to live on the reservation and decided too find work or make a separate life for themseleves in the urban area's of the US.

Of course, that is not too say, it is just in Oklahoma where you would still be able too find a strong influence of US native americans. There is also New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, parts of Texas and ect... and so on! But i guess you get my point?

|

Posted By: Guests

Date Posted: 05-Nov-2007 at 00:33

Originally posted by Panther

Not to be unfairly critical pinguin, but your poll could have used a little more brushening up? As it currently stands, i would have to go with the end result of the policy, which is too make them sadly dependent on the good or bad will of the state. A very good case of not allowing this country's government too keep growing into the ultimate nanny state, if i ever saw one?!

Was it genocide? Only against the North American bison. Genocide against the Indians? No, i think that pretty much misses the point of the ultimate aim of the US government in bringing the centuries long war with the indigenous population too an end! Did it destroy their culture and way of life? For some it unarguably did. But for many other tribes, it only weakened them to a certain extent of acquiescence, but did not in the end, destroy them or their belief's!

Case in point, i know quite a few guys who are life long card carrying members of any one particular tribe (But, predominantly cherokee or comanche), but in this point of reference, i am talking about Oklahoma... who still attend their ancestors tribal ritual gatherings. That is... they are theones who chose not to live on the reservation and decided too find work or make a separate life for themseleves in the urban area's of the US.

Of course, that is not too say, it is just in Oklahoma where you would still be able too find a strong influence of US native americans. There is also New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, parts of Texas and ect... and so on! But i guess you get my point? |

Well, you have more direct refferences than myself in the topic because you live in the U.S. and know in detail what happened in there.

I made the poll thinking in the average citizen of the world that wonders why the buffalo was driven to the edge of extinction and how it affected the Indians that lived of them. I just supossed that some people died of hunger because theirs source of food was driven to extinction.

From my personal point of view, I don't consider the changing of cultures a "cultural genocide" as it is in fashion to say. I am just concern in the real extermination of people, that existed sometimes, but that in the case of the American Indians across the hemisphere, is very confussing and more than once the information has been manipulated by political reasons.

Just as an example, it is well known that the Tainos of the Caribbean didn't become extinct but assimilated... but you hear once and once again the same story repeated thousand of times in the books.

Researching the extinction of the Kawashkar in Austral Chile, for instance, I found out there were 2.000 people at time of contact. Today they are extinct, but 4.000 mixed descendents still live in the area and many more migrated to other latitudes. So, do they really become extinct?

Above all, I am interested to know if there was really a genocide in the United States. The more I get into it, the more that it looks to me that Amerindians assimilated, and many become just regular "white" people that married immigrants.

|

Posted By: Panther

Date Posted: 05-Nov-2007 at 01:41

The same could be said by me, regarding your knowledge of your particular region. I know very little, or next to nothing, as compared too your direct experiences of living there within the region; Hence... i always "try" too defer to your knowledge; That is... if my knee jerk reactions don't get the better of me first?

All around, really fascinating stuff!

|

Posted By: Guests

Date Posted: 05-Nov-2007 at 03:27

|

Agree!

Fascinating. Besides, there is lot of research to be done before the matter really settles.

|

Posted By: The Canadian Guy

Date Posted: 06-Nov-2007 at 18:16

They were killed only to starve the peoples who fondly ate and used their bones.

-------------

Hate and anger is the fuel of war, while religion and politics is the foundation of it.

|

Posted By: Paul

Date Posted: 14-Nov-2007 at 03:33

Regionally it varied. But the extermination of the Buffalo was in part used to kill off the Komanche, and a damn good thing too.

-------------

Light blue touch paper and stand well back

http://www.maquahuitl.co.uk - http://www.maquahuitl.co.uk

http://www.toltecitztli.co.uk - http://www.toltecitztli.co.uk

|

Posted By: Guests

Date Posted: 14-Nov-2007 at 10:11

Originally posted by Paul

Regionally it varied. But the extermination of the Buffalo was in part used to kill off the Komanche, and a damn good thing too. |

What do you mean? I hope not what I think you do.

|

Posted By: Adalwolf

Date Posted: 14-Nov-2007 at 15:41

Originally posted by pinguin

Originally posted by Paul

Regionally it varied. But the extermination of the Buffalo was in part used to kill off the Komanche, and a damn good thing too. |

What do you mean? I hope not what I think you do. |

Yes, please explain. I don't see how almost exterminating an entire species is a good thing, especially to hurt a group of people who depend on that species.

Please explain...in detail.

-------------

Concrete is heavy; iron is hard--but the grass will prevail.

Edward Abbey

|

|